The intertwined fate of heart, kidneys, and metabolism: Mastering risk mitigation in high-risk patients

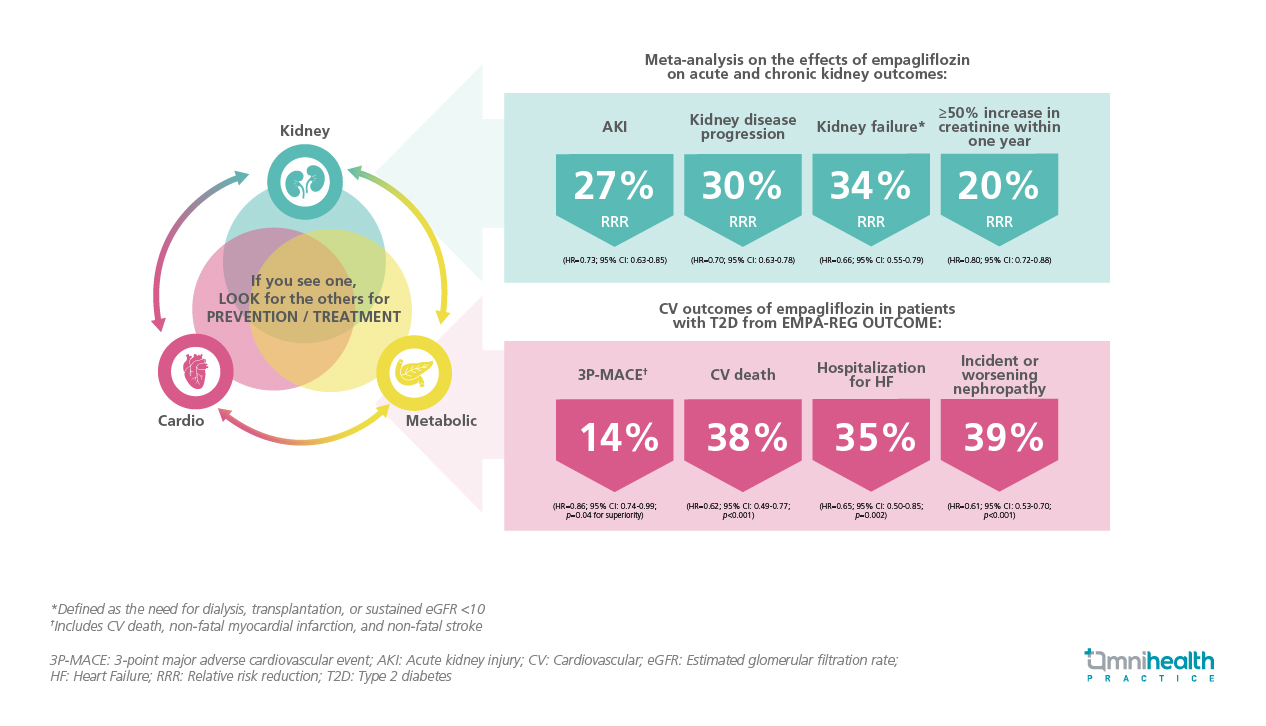

For decades, clinicians have treated cardiovascular (CV), renal, and metabolic diseases as separate entities, managed by different specialists.1 However, these conditions are not merely comorbidities; they form a deeply interconnected system.1,2 This understanding represents the unified concept of cardio-kidney-metabolic (CKM) syndrome.1,2 In a recent lecture, Dr. Cheng, Yuk Yan Alice from the University of Toronto, explained that CKM syndrome is not a new disease but rather a “new recognition” of the longstanding truth that these organ systems are interconnected in a pathological feedback loop. The profound interconnectedness of CKM necessitates a unified approach to screening and treatment.2 This paradigm shift is evidenced by the unexpected yet encouraging data from the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial, further solidified in the EMPA-HF trials, and culminating in landmark studies like EMPA-KIDNEY.3-7 These developments have repositioned empagliflozin as part of a new class of “organ-protecting” drugs.

The interconnectedness of CKM diseases

Metabolic health is a key determinant of kidney function, with around 40% of individuals with type 2 diabetes (T2D) also experiencing chronic kidney disease (CKD).8 The relationship between the heart and metabolism is similarly notable, as approximately one in three individuals with T2D also have CVD.9 There is significant overlap among CKM diseases, with up to 63% of individuals with CKD also having cardiovascular disease (CVD).10 Additionally, 20%-40% of patients with heart failure (HF) also have T2D, and 50% of patients with HF have coexisting CKD.11,12

This dense web of overlapping conditions is no coincidence. Dr. Cheng pointed out that this interrelationship reflects the shared underlying pathogenesis of these conditions. Metabolic dysfunction, including lipo- and glucotoxicity associated with diabetes, contributes to oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction, which can lead to both kidney and heart disease.1 She highlighted that impaired kidney function, in turn, results in chronic inflammation and the accumulation of uremic toxins, which further exacerbate metabolic dysfunction and worsen cardiac function through mechanisms such as salt and water retention. This decline in cardiac function can lead to low output and overactivation of the sympathetic nervous system, which subsequently causes additional damage to the kidneys, perpetuating the cycle. This significant global burden, driven by a complex cycle of mutual organ damage, underscores the importance of early and comprehensive screening as a critical first step in managing CKM.1

CKM screening beyond a singular diagnosis

A key takeaway from the CKM framework is the importance of early and comprehensive screening as a fundamental first step.1 Dr. Cheng emphasized the necessity of proactive screening, stating, “If you see one condition, look for the others. This search must begin before CKM fully manifests. It is essential for healthcare providers to identify all related conditions and initiate treatment early.” To identify at-risk individuals, Dr. Cheng highlighted the limitations of traditional body mass index (BMI), which may overestimate risk in muscular individuals and underestimate it in East and South Asian populations. A more effective and reliable measure is the waist-to-height ratio (WHtR), which should ideally be less than 0.5.13,14

Once metabolic risk factors such as hypertension, T2D, or CKD are identified, screening becomes increasingly critical, particularly for kidney health.1,15 Dr. Cheng reminded that at earlier stages, clinicians often make a significant oversight by assessing the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) without also evaluating the urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR). To illustrate the importance of both eGFR and UACR, Dr. Cheng employed a "train analogy": “Imagine a train station called 'Dialysis.' The eGFR indicates how far the train is from the station, but the UACR provides critical information about the train's speed.”15 Without the UACR, high-risk patients who have a good eGFR but a high UACR may go undetected. Therefore, to accurately assess risk, both eGFR and UACR are necessary.15 Recognizing this interconnected risk was only part of the challenge; a unified solution for CKM was needed. This breakthrough arrived in 2015 with the introduction of empagliflozin.3

Empagliflozin: A significant advancement in diabetes management

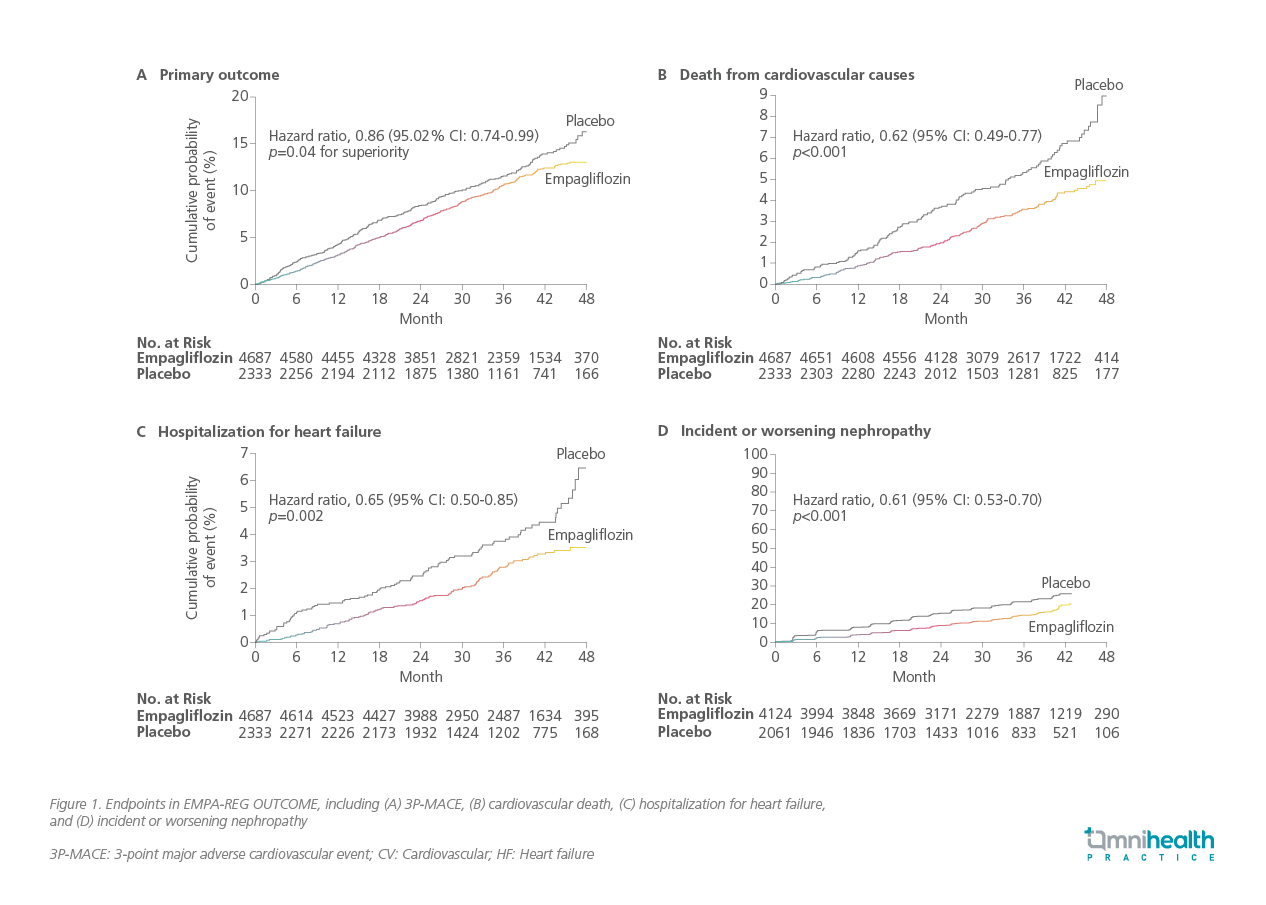

Dr. Cheng noted that while there have been effective medications to lower blood glucose levels, few have demonstrated the ability to protect the organs affected by diabetes. At the 2015 European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) conference in Stockholm, the results of the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial were presented. Dr. Cheng remarked, “Initially regarded as a routine CV safety study for empagliflozin in patients with T2D, the results were significant, as this was the first time an anti-hyperglycemic drug was shown to reduce major adverse outcomes independent of its glucose-lowering effect.” The study indicated a 14% relative risk reduction (RRR) in 3-point major adverse cardiovascular events (3P-MACE), which includes CV death, non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI), or non-fatal stroke (HR=0.86; 95% CI: 0.74-0.99; p=0.04 for superiority).3 Additionally, there was a 38% RRR in CV death (HR=0.62; 95% CI: 0.49-0.77; p<0.001), a 35% RRR in hospitalization for HF (HR=0.65; 95% CI: 0.50-0.85; p=0.002), and a 39% RRR in incident or worsening nephropathy (HR=0.61; 95% CI: 0.53-0.70; p<0.001) (figure 1).3,4 Dr. Cheng noted that “This is not just a diabetes medication; it is also an organ protection therapy.” This study prompted a series of new trials to investigate sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors for heart and kidney diseases independent of diabetes.

Following the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial, a substantial amount of evidence emerged, demonstrating that the SGLT2 inhibitor class was rigorously tested across the entire CKM spectrum.5-7 The evidence for HF benefits was compelling enough to support trials in patients both with and without diabetes, including the EMPEROR-Reduced and EMPEROR-Preserved trials.5,6 For HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), this was particularly noteworthy, as Dr. Cheng claimed, “there were previously no treatments that effectively improved outcomes.” The number needed to treat (NNT) was found to be 18 in HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and 34 in HFpEF to prevent a primary outcome event.16 The evidence for organ protection extended beyond CV outcomes; the findings regarding kidney protection were equally robust, further solidifying the role of empagliflozin as a significant therapy in CKM management.7

From CV to kidney: Empagliflozin shows broad renal protection across diverse populations

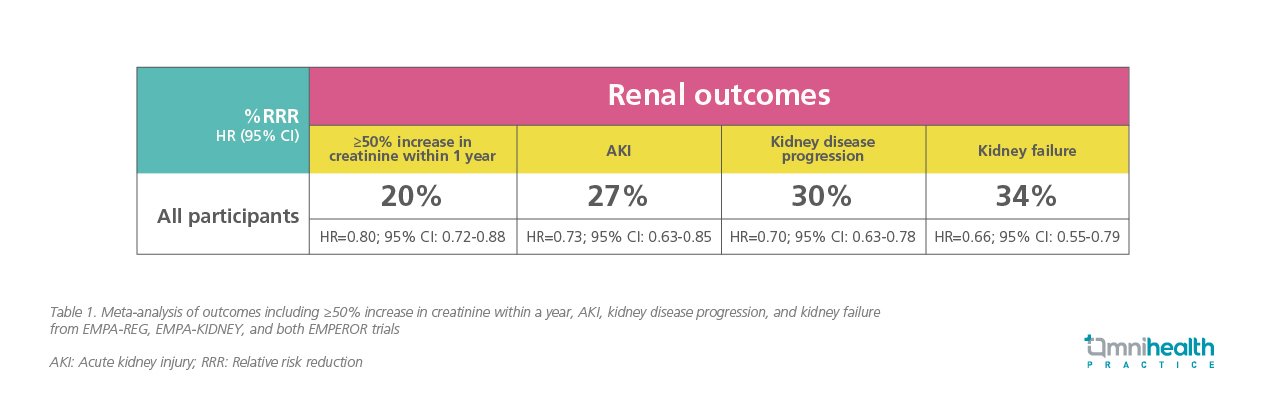

Evidence for organ protection extended beyond CV outcomes as demonstrated by the significant EMPA-KIDNEY trial. The trial studied the broadest population to date. This trial included patients with an eGFR as low as 20mL/min/1.73m² and critically included patients with low or no albuminuria—a group that was excluded from previous studies.17 In the EMPA-KIDNEY population, the results were definitive, showing a 28% RRR in the progression of kidney disease or CV death.7 She claimed that, “The data also indicated that empagliflozin was effectively saving nephrons, evidenced by a significantly flatter slope of eGFR decline over time.” This evidence was further reinforced by a large participant-level meta-analysis published in late 2025, which combined data from the EMPA-REG, EMPA-KIDNEY, and both EMPEROR trials.18 This analysis, involving over 23,000 patients, provided the most robust evidence to date, demonstrating that empagliflozin significantly reduced the most critical kidney endpoints.18

The analysis reported a 27% RRR in acute kidney injury (AKI), a 30% RRR in kidney disease progression, a 34% RRR in kidney failure (defined as the need for dialysis, transplantation, or sustained eGFR <10), and a 20% RRR in a ≥50% increase in creatinine within one year (table 1).18 Importantly, the benefits were consistent "irrespective of the subgroup," indicating effectiveness regardless of whether patients had diabetes, their UACR, eGFR levels, or the presence of HF.18

A new standard of care and a shared responsibility

The evidence supporting SGLT2 inhibitors is now so compelling that they are recognized as foundational therapy for organ protection, rather than merely "sugar drugs." This shift in understanding is reflected in major international guidelines.19-22 The 2021 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines recommend SGLT2 inhibitors with a class 1 (strongest) recommendation for HFrEF patients to reduce mortality and the focused update in 2023 extended the recommendation to HFpEF patients to reduce hospitalization or CV death, with additional recommendations on initiating SGLT2 inhibiters to reduce the risk of HF hospitalization or CV death in patients with T2DM and CKD.19,20 Similarly, the 2024 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines strongly recommend SGLT2 inhibitors for patients with T2D and CKD.21 They also recommend them for CKD patients without diabetes who have albuminuria or HF.21 Lastly, the American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes (ADA/EASD) consensus guidelines recommend SGLT2 inhibitors for patients with T2D who have CKD, HF, or high atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk, regardless of their glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels or metformin use.22

Conclusion

Supported by robust evidence from landmark trials like EMPA-REG OUTCOME, EMPA-HF, and EMPA-KIDNEY, empagliflozin is now a foundational, guideline-recommended therapy for CKM conditions.3-7,19-22 Dr. Cheng remarked that “This new standard of care brings a shared responsibility that transcends any single specialty. It is a collective duty for endocrinology, cardiology, nephrology, and primary care, unified by a simple principle: any clinician who identifies the need for this organ-protective therapy should be the one to initiate it.

- Ndumele CE, et al. Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Health: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2023;148(20):1606-1635.

- Lee CH, et al. Incorporating the cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic health framework into the local healthcare system: a position statement from the Hong Kong College of Physicians. Hong Kong Med J. 2025;31(1):58-64.

- Zinman B, et al. Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2117-28.

- Wanner C, et al. Empagliflozin and Progression of Kidney Disease in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):323-34.

- Anker SD, et al. Empagliflozin in Heart Failure with a Preserved Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(16):1451-1461.

- Packer M, et al. Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes with Empagliflozin in Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(15):1413-1424.

- Herrington WG, et al. Empagliflozin in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(2):117-127.

- Shubrook JH, et al. Management of chronic kidney disease in type 2 diabetes: screening, diagnosis and treatment goals, and recommendations. Postgrad Med. 2022;134(4):376-387.

- Einarson TR, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes: a systematic literature review of scientific evidence from across the world in 2007-2017. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):83.

- Lovre D, et al. Managing Diabetes and Cardiovascular Risk in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2018;47(1):237-257.

- Thomas MC. Type 2 Diabetes and Heart Failure: Challenges and Solutions. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2016;12(3):249-55.

- Szlagor M, et al. Chronic Kidney Disease as a Comorbidity in Heart Failure. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(3):2988.

- Browning LM, et al. A systematic review of waist-to-height ratio as a screening tool for the prediction of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: 0.5 could be a suitable global boundary value. Nutr Res Rev. 2010;23(2):247-69.

- Kazlauskaite R, et al. Race/ethnic comparisons of waist-to-height ratio for cardiometabolic screening: The study of women's health across the nation. Am J Hum Biol. 2017;29(1):10.1002/ajhb.22909.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Quick Reference on UACR & GFR In Evaluating Patients with Diabetes for Kidney Disease Urine Albumin-to-Creatinine Ratio (UACR). Available at: https://rb.gy/nm8t4c. Updated Mar 2012. Viewed Nov 2025.

- Chen K, et al. Time to Benefit of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors Among Patients With Heart Failure. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(8):e2330754.

- Forbes AK, et al. A comparison of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor kidney outcome trial participants with a real-world chronic kidney disease primary care population. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2024;40(1):71-82.

- Herrington WG, et al. Effects of empagliflozin on conventional and exploratory acute and chronic kidney outcomes: an individual participant-level meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025;13(12):1003-1014.

- McDonagh TA, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(36):3599-3726.

- McDonagh TA, et al. 2023 Focused Update of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2023;44(37):3627-3639.

- CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2024;105(4S):S117-S314.

- Davies MJ, et al. Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes, 2022. A Consensus Report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2022;45(11):2753-2786.