MEETING HIGHLIGHT

New paradigms in hepatitis management to address treatment challenges and barriers to care

In a webinar organized by the Hong Kong Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (HKASLD), Professor Kim, Seung-Up and Dr. Wong, Yu-Jun Eugene introduced the new paradigms in viral hepatitis disease control. While Prof. Kim discussed some topics of hepatitis B virus (HBV) management, including the increased risk of kidney disease with long-term antiviral use and the appropriate first-line agents to mitigate this risk, Dr. Wong presented the challenges of hepatitis C virus (HCV) management and access to care, highlighting the efficacy and safety of the direct-acting antiviral (DAA) treatment of sofosbuvir/ velpatasvir (SOF/VEL) in HCV patients and the simplified treatment monitoring in reducing the healthcare burden.

Renal risks in HBV management

HBV is a chronic disease requiring antiviral medications for long-term or lifelong suppressive treatment.1 Despite the current evolution of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) medications, there is still no cure.1 The guidelines and studies on CHB indicate that patients receiving certain long-term anti-HBV medications may experience renal function and bone mineral density decline.1 Since many CHB patients often require lifelong antiviral therapy, the potential risk of kidney impairment associated with long-term treatment remains a concern.

Prof. Kim shared an analysis of a large United States (US) administrative healthcare claims database from 2006 to 2015, demonstrating that the prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) among CHB patients increased over time and was higher than that in non-CHB controls at several time points in 2006, 2010 and 2015.1 Hence, it is essential to assess the renal function in patients for the sake of reducing the risk of renal function decline among CHB patients.

According to the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) guidelines on HBV management, the first-line treatment options should include the potent nucleos(t)ide analogs (NAs) with high barrier to resistance, such as tenofovir alafenamide (TAF), tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) and entecavir (ETV) monotherapies, due to their tolerability and predicted long-term antiviral efficacy achieving undetectable HBV deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) levels in compliant patients.2 In the subgroups of CHB patients, both ETV and TAF are preferred over TDF since patients on TDF are at the risk of underlying renal or bone disease.2

Minimizing treatment-associated risks with TAF

A prospective study among Japanese showed that CHB patients switching from ETV to TAF had a significantly greater reduction in the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) levels during the TAF phase than the ETV phase. However, there were no significant differences in the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) decline during both phases at year 1.3

Another retrospective, multicenter, cohort study was conducted to evaluate the virological and biochemical effects, as well as the renal safety of patients switching from ETV or NA combination therapy to TAF monotherapy for at least 2 years.4 Results showed that switching to TAF demonstrated a continued HBV suppression with the reduction in HBsAg level, regardless of the baseline HBsAg level, even in patients with partial response to previous therapy.4 The switching also resulted in alanine transaminase (ALT) normalization and a significant improvement in eGFR among CKD patients treated with an NA combination previously.4

Moreover, an international study involving 425 patients who switched to TAF from an average of 6 years of ETV treatment resulted in a statistically significant increase in complete viral suppression without any significant change in CKD stage.5

Prof. Kim and his colleagues also published a retrospective, longitudinal cohort that compared the risk of kidney function decline among treatment-naïve CHB patients receiving ETV or TAF.6 Of the 1,988 recruited patients, 1,839 were treated with ETV and 149 were treated with TAF.6 A 1:1 propensity score match was used to match the 2 groups, which were balanced in terms of baseline covariates.6 The primary outcome was CKD progression, defined as ≥1 CKD stage increase for at least 3 consecutive months during the follow-up.6 Out of the 149 patients in the matched cohort, 47 patients in the ETV group [19.9 per 1,000 person years (PYs); 95% CI: 15.0-26.5] and 14 patients in the TAF group (5.1 per 1,000 PYs; 95% CI: 3.0-8.6) developed progression in CKD stage ≥1 (p<0.001) (figure 1).6

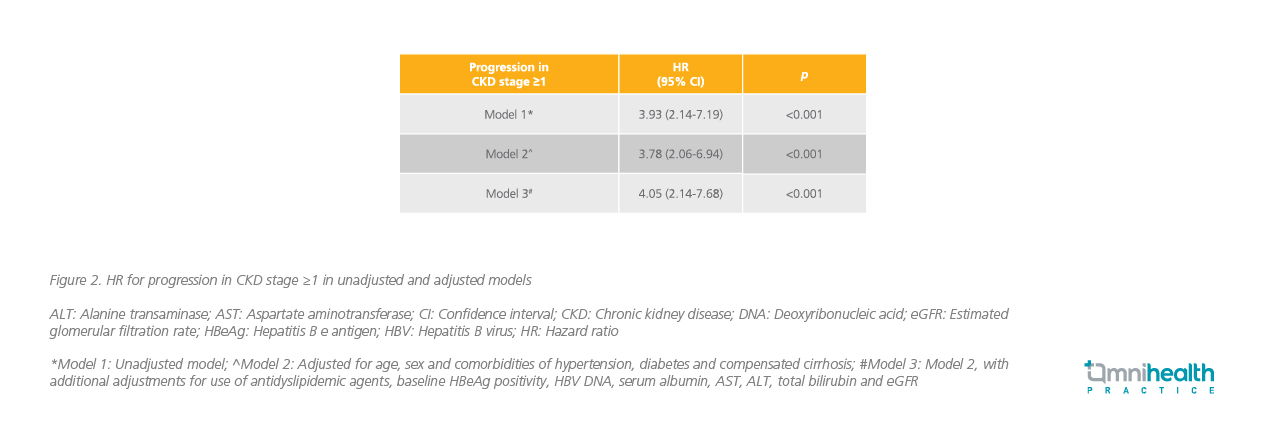

The cumulative incidence of progression in CKD stage ≥1 was significantly higher in the ETV group compared with the TAF group (p<0.001).6 The unadjusted hazard ratio (HR) for progression in CKD stage ≥1 was 3.93 (95% CI: 2.14-7.19; p<0.001).6 After adjustment for potential confounders such as age, sex, underlying comorbidities, baseline eGFR, and HBV DNA levels, similar findings were noted with an adjusted HR (aHR) of 4.05 (95% CI: 2.14-7.68; p<0.001) (figure 2).6

The study also compared outcomes in 1,839 patients treated with ETV and 1,061 CHB control patients not receiving any treatment.6 A total of 354 patients in the ETV group and 63 patients in the untreated group developed progression in CKD stage ≥1 (3.2 vs. 1.2 per 1,000 PYs; p<0.001). This association was statistically significant even with the adjustment for potential confounders (aHR=2.37; 95% CI: 1.74-3.23; p<0.001).6

Challenges and barriers in access to care and HCV management

Similarly, HCV is another bloodborne pathogen with a globally estimated number of patients decreased from 71 million in 2015 to 58 million in 2019.7,8 DAA has revolutionized the HCV treatment landscape.9 Despite improvement in the HCV treatment, access to diagnosis and treatment remains low.7 To address this, Dr. Wong shared his view on the challenges of HCV management and access to care.

According to Dr. Wong, an ideal DAA should have high efficacy against all genotypes with a high barrier of resistance and minimal drug-drug interactions (DDIs). Besides, it should be easy to use, both for patients and physicians. Thus, having one-pill once-daily dosing, a short treatment duration and being ribavirin free are the attractive reasons when it comes to using DAAs.

In the past, both the treatment cost and accessibility were the major challenges to global HCV eliminations, and that limited progress has been made in the global adoption of HCV treatment because of the barriers to treatment scale-up, such as the availability and access to diagnostic and monitoring tests, healthcare infrastructure and requirement for frequent visits during treatment.10 In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) adopted the first global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis, proposing the elimination of viral hepatitis including HCV as a public health threat by 2030.7 To achieve the HCV elimination goal, collaboration from various stakeholders, establishing evidence-based policy, mobilizing resources, increasing health equities, and scaling up screening, care and treatment services are needed.7

Based on the WHO global progress report, currently nearly 80% of global HCV patients come from low- and middle-income countries, where pretreatment genotyping and multiple treatment monitoring costs are sometimes even higher than the medication costs.11 Hence, it is important to simplify pretreatment diagnosis and processes in sophisticated laboratories so that results could be provided in a single visit, also allowing treatment access to more patients.11

Overcoming barriers in HCV management in the real world

“Some of us may be deciding whether to perform genotyping before HCV treatment. As clinicians, we want to maximize the likelihood of sustained virologic response (SVR) in every patient. So, genotyping may be helpful, particularly for patients with genotype 3b (GT3b) and when cirrhosis is prevalent,” Dr. Wong highlighted. He also emphasized that pretreatment genotyping should be reconsidered since it can lead to delay in treatment and add to the cost of treatment in patients.

With the goal of curing HCV, the most commonly used DAA regimen is SOF.7 Clinical trials and real-world studies have shown that SOF and VEL combination was an efficacious and safe DAA treatment option in GT3 HCV, which is the predominant genotype in the Singapore population, even with compensated or decompensated cirrhosis.

An observational, retrospective study was performed on all GT3 HCV patients treated with 12 weeks of SOF/VEL (400mg/100mg), with or without weight-based ribavirin (RBV), to assess the efficacy and safety of SOF/VEL ± RBV in the real-world setting.12 The primary outcome was the overall SVR 12 weeks after treatment (SVR12) and the secondary outcomes were the SVR12 in the subgroup analysis and the occurrence rate of serious adverse events (SAEs).12 The overall SVR12 in GT3 HCV patients was 98.7% (95% CI: 97.3%-99.5%) and 99.2% (95% CI: 98.1-99.8%) in the intention-to-treat (ITT) and per protocol analyses, respectively.11 The subgroup analysis demonstrated a high SVR12 among GT3 HCV patients with decompensated cirrhosis (88%), prior treatment (100%), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (100%), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/HBV coinfection (100%).11 SOF/VEL ± RBV was found to be safe with no SAEs, except myositis in 1 patient.12

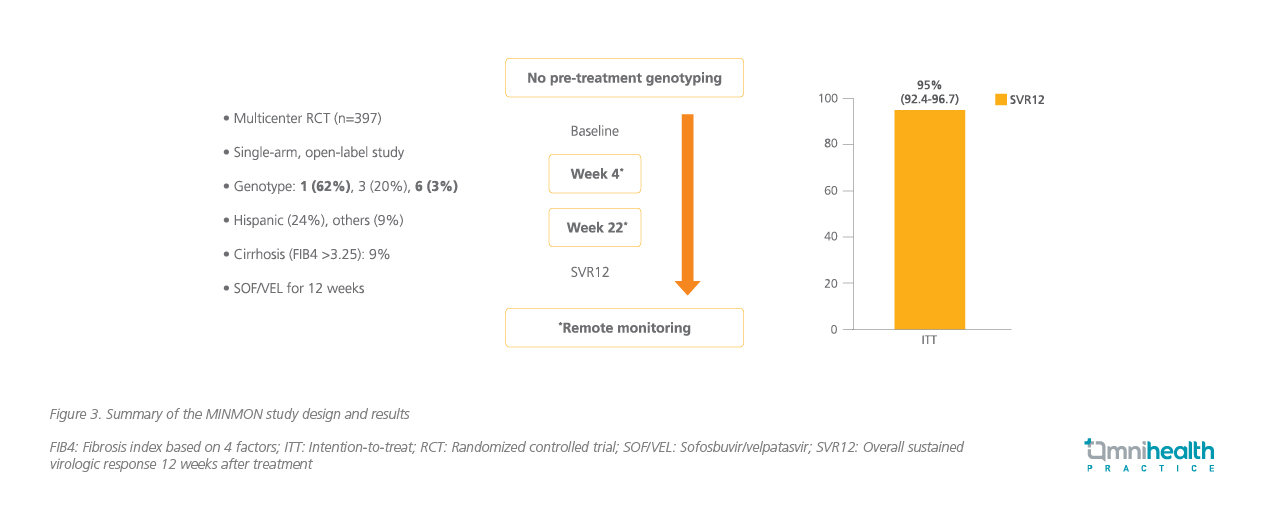

Dr. Wong stressed that it is necessary to simplify the treatment in order to screen and treat more patients at the same time, thus achieving the WHO goal of HCV elimination. Therefore, the MINMON study, a phase 4, open-label, single-arm, multinational trial, was conducted to examine the efficacy and safety of a minimal monitoring approach of delivering interferon-free and ribavirin-free, pan-genotypic DAA to treatment-naïve patients with active HCV infection defined as ribonucleic acid (RNA) >1,000IU/mL.10 This study specifically included countries from low-to-middle income countries, such as Brazil and Thailand.10 All included patients received a single tablet of fixed-dose combination of SOF 400mg/VEL 100mg taken orally once daily for 12 weeks, and they were only physically reviewed at baseline and SVR12, then the visit was replaced by simple monitoring using phone call or email to assess the patient’s compliance and presence of adverse event during the treatment.10

The primary efficacy outcome was SVR, defined as plasma HCV RNA less than the assay’s lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) at least 22 weeks and up to 72 weeks following treatment initiation and SAEs.10 Of the 399 patients who started the treatment, 379 patients (95%) had an SVR (95% CI: 92.4-96.7) (figure 3).10 Similarly, 88.2% of patients with hepatic cirrhosis achieved an SVR (95% CI: 73.4-95.3).10 SAEs were reported in 14 patients (4%) between initiation and week 28, but they were not treatment-related or leading to treatment discontinuation or death.10

Implications of remote monitoring

Dr. Wong also discussed his experience with simplified monitoring in HCV treatment in Singapore. He and his colleagues conducted a retrospective analysis of the HCV registry in Singapore between 2019 and 2021, with the aim of comparing simplified monitoring with the standard of care (SoC) monitoring. Patients who underwent simplified monitoring had a comparable SVR to those who received SoC monitoring.

In fact, based on the current American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)/Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines, treatment naïve patients with any fibrosis stage up to compensated cirrhosis may be also considered for simplified monitoring.13 In contrast, patients who have prior HCV treatment, current pregnancy, end-stage renal disease (i.e., eGFR <30mL/min/m2), prior or current episodes of decompensated cirrhosis, HIV/HBsAg positive, known or suspected HCC, or prior liver transplantation are ineligible for simplified monitoring.13 For patients eligible for simplified monitoring, pretreatment assessments should be performed, including the assessment for decompensated liver cirrhosis and HCC.13 Medication reconciliation, assessment for potential DDI and education to prevent reinfection should also be performed.13

Lastly, Dr. Wong emphasized that pretreatment genotype testing should be conducted when the local prevalence of GT3b >5%. In Singapore where GT3a is the most common HCV genotype, routine HCV genotyping may not be required. Following the assessment, recommended treatments (e.g., SOF/VEL for 12 weeks) can be initiated.13 During the treatment monitoring period, it is also important to monitor the international normalized ratio (INR) in patients on warfarin and hypoglycemia in patients on diabetes medications.13

Conclusion

In HBV, TAF was shown to be superior to ETV in terms of renal safety with proven efficacy from clinical trials and several real-world studies. Since CHB requires long-term or lifelong treatment with antivirals that are associated with nephrotoxicity, it is important to select a first-line treatment option with low risk of renal deterioration such as TAF. In HCV, SOF/VEL ± RBV has demonstrated efficacy in achieving SVR with a tolerable safety profile. Simplified remote monitoring is a safe and efficacious treatment strategy for HCV patients in the real world, even in the rural setting, and may reduce the healthcare burden and facilitate treatment upscale for HCV elimination.