EXPERT INSIGHT

Protecting children from the looming threat of MIS-C during the COVID-19 pandemic

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) is a novel post-infectious inflammatory condition associated with Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), characterized by prolonged fever, gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms and rash.1 To some extent, the disease resembles Kawasaki disease (KD), toxic shock syndrome (TSS), and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), increasing the difficulty in differential diagnosis in clinical practice.1 In an interview with Omnihealth Practice, Dr. Cheung, Wai-Yin Eddie discussed the challenge of evaluating suspected MIS-C cases in real-life scenarios and emphasized the importance of timely intervention among children who were infected with or recently recovered from COVID-19. He also shared a clinical case of a 7-year-old girl with MIS-C who presented with early MIS-C symptoms and was managed with immunomodulatory treatment, swiftly achieving favorable outcomes.

MIS-C: The delayed consequence of COVID-19 among children

While elderly people are at increased risk of substantial mortality after being infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), severe acute disease among children is relatively rare.1 Nevertheless, during the peak of COVID-19 pandemic in Europe in 2020, a cluster of children was found to have developed hyperinflammatory syndrome and shock 2-4 weeks after recovering from acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, which was later termed as MIS-C by the United States (US) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).2 As of December 2021, a total of 8,525 MIS-C cases had been reported in the US, which included 69 deaths, and 58% of the patients were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU).2 All patients were positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection (98%) or in close contact with someone with COVID-19 (2%).2 The majority of these children presented MIS-C at a median age of 9 years with abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, skin rash, conjunctivitis, and hypotension.2 Some children with MIS-C even developed severe complications, such as cardiac dysfunction (40.6%), shock (35.4%), myocarditis (22.8%), and coronary artery dilation/aneurysm (18.6%) (figure 1).2

Clinical evaluation of suspected MIS-C cases and differential diagnosis

Since MIS-C patients may quickly deteriorate into critical condition, it is crucial to confirm the diagnosis as soon as possible and intervene early.3 Suspected MIS-C cases should be evaluated for generalized inflammation, multisystem involvement and possible infection.3 In particular, clinicians are recommended to pay attention to cardiac function, respiratory status, neurological status, and renal function.3 Consultation with specialists in multiple disciplines, including pediatric intensive care, cardiology, rheumatology, infectious disease, and immunology, might be required.3 As mentioned, MIS-C resembles other inflammatory syndromes.3 Table 1 illustrates the clinical differences between MIS-C and other similar diseases.3

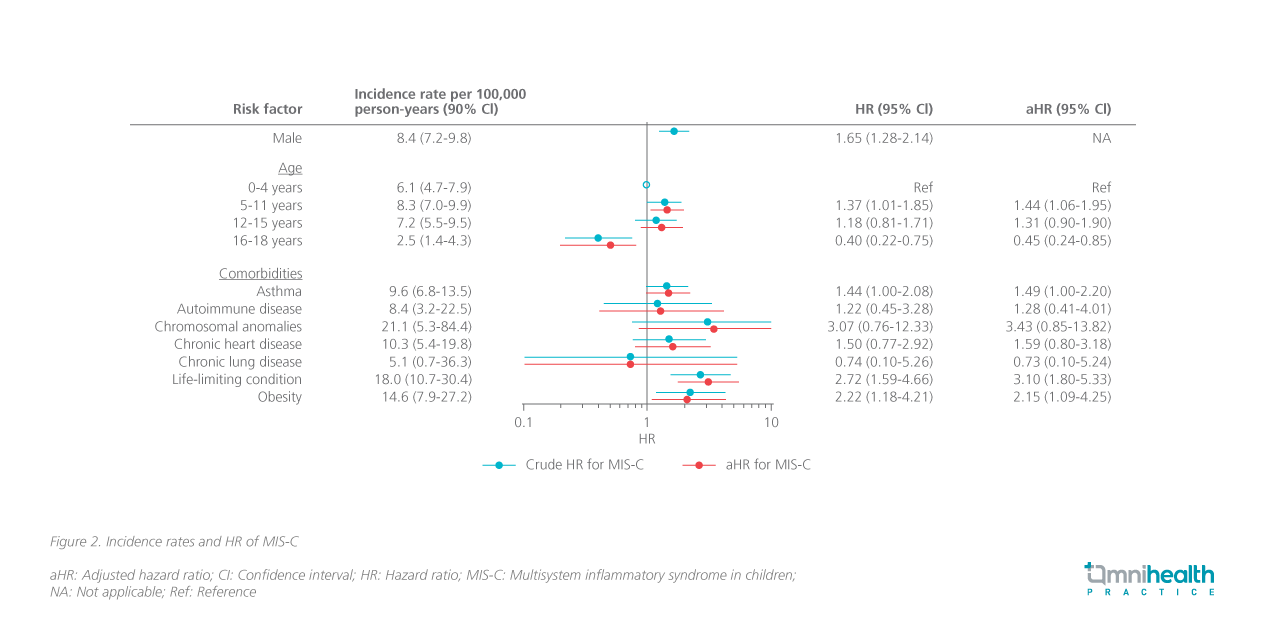

Higher alertness of MIS-C needed for children with risk factors

A large Swedish cohort study was performed to assess the risk factors of MIS-C for identifying vulnerable children.1 This study involved 2,117,443 children with comorbidities, including asthma, autoimmune disease, chromosomal anomalies, chronic heart disease, chronic lung disease, obesity, and other life-limiting conditions.1 A total of 253 children developed MIS-C, corresponding to an incidence rate of 6.8 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI: 6.0-7.6).1 Results found that children aged 5-11 years were 44% more likely to develop MIS-C vs. children aged 0-4 years [adjusted HR(aHR)=1.44; 95% CI: 1.06-1.95].1 In addition, the male sex was also associated with a 65% elevated risk of MIS-C vs. female (HR=1.65; 95% CI: 1.28-2.14).1 Children with asthma (aHR=1.49; 95% CI: 1.00-2.20), obesity (aHR=2.15; 95% CI: 1.09-4.25), or a life-limiting condition (aHR=3.10; 95% CI: 1.80-4.25) were also found to be more susceptible to MIS-C (figure 2).1 Dr. Cheung reminded that parents should be more alert when high-risk children develop early symptoms and should seek medical attention accordingly.

Pharmacological management of MIS-C

IVIG monotherapy

Thanks to the well-established safety profile and proven benefit of intravenous (IV) immunoglobulin (IG) in reducing the risk of coronary artery aneurysms in patients with KD, the international guidelines continue to recommend using IVIG as the first-line treatment in the management of MIS-C.4 In a series of 539 MIS-C cases where the majority of patients received IVIG (77%) and 34.2% of patients presented with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) at hospital admission.4 Upon treatment with IVIG, ≥90% of patients had their symptoms resolved by day 30.4 In general, IVIG is given at a single dose of 2g/kg up to a maximum dose of 100g.4 During IVIG infusion, patients’ cardiac function and fluid status should be monitored closely.4

The combination of IVIG + glucocorticoids

Thus far, no randomized clinical trials evaluating IVIG + glucocorticoids for the treatment of MIS-C have been conducted.4 However, multiple non-randomized studies found that front-line IVIG + low-to-moderate-dose glucocorticoids were associated with less treatment failure, faster recovery of cardiac function, shorter ICU stay and decreased requirement for treatment escalation vs. IVIG monotherapy.4 Based on the published data, guidelines recommend the IVIG-glucocorticoids combination regimen for children hospitalized with MIS-C (i.e., more severe disease).4 Methylprednisolone is the most commonly used steroid and is administered at a dose of 1-2mg/kg/day until the child patient becomes afebrile.4

Treatment escalation in unresponsive children with MIS-C

Typically, children with MIS-C respond quickly to the prescribed immunomodulatory therapy within the first 24 hours, characterized by resolution of fever, improvement of organ function and reduced levels of inflammatory markers [e.g., C-reactive protein (CRP)].4 For patients with persistent symptoms, worsening organ dysfunction, or increasing levels of biomarkers despite front-line treatment, intensification therapy is urgently needed since the decline in clinical status among children with uncontrolled MIS-C can be quite rapid.4 The international guidelines recommend adding anakinra, higher-dose glucocorticoids or infliximab to the regimen.4 In certain patients with more severe disease, dual therapy with higher-dose glucocorticoids + anakinra or infliximab can be considered (note: Anakinra and infliximab should never be used in combination).4 A second dose of IVIG is generally not recommended in refractory MIS-C due to high rates of IVIG resistance, rapid disease escalation and the risk of fluid overload in MIS-C patients.4 Dr. Cheung cautioned that patients who receive multiple immunomodulatory agents are at risk of infection and should be monitored carefully.

Dr. Cheung stressed that alertness is the key to protecting children from severe complications associated with MIS-C. “Early signs of MIS-C include fever, red eyes or skin rash. When they occur, parents and clinicians should be aware of the possibility of MIS-C and perform thorough medical check-ups as early as possible,” Dr. Cheung emphasized. Delayed diagnosis of MIS-C could lead to a higher likelihood of serious complications and increase the need for treatment escalation. During the interview with Omnihealth Practice, Dr. Cheung shared a clinical case of a 7-year-old girl with MIS-C who presented with early MIS-C symptoms and was managed with IVIG alone, quickly achieving favorable outcomes.

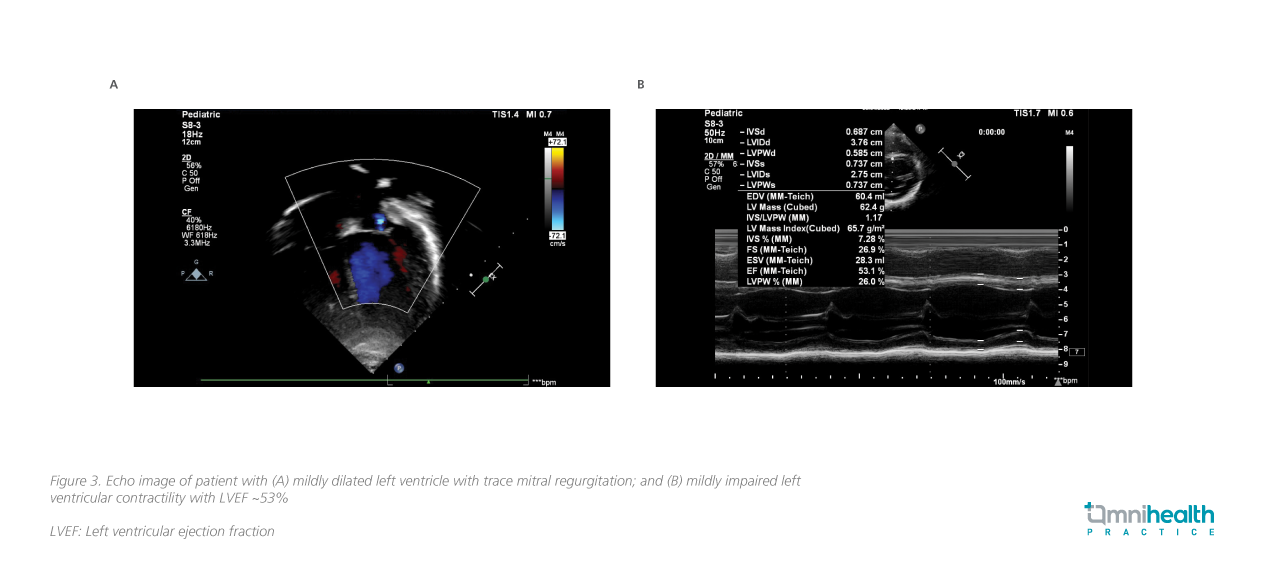

Case sharing: Early identification of MIS-C improves outcomes

In September 2022, a 7-year-old girl presented with recurrent fever, rash, conjunctivitis, and abdominal discomfort 5 weeks after recovering from COVID-19. Since public awareness of MIS-C has increased, the girl’s parents promptly sought medical attention when the symptoms were still mild. Upon initial medical evaluation, biochemistry showed an elevated level of CRP of 75.5mg/L. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 48mm/hour at presentation. The patient was also found to have increased levels of ferritin, N-terminal-pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and D-dimer, but with a low platelet count. Initial echocardiogram showed mildly impaired left ventricular contraction but normal coronary arteries (figure 3). The diagnosis of MIS-C was confirmed.

Since the case was discovered early and was mild in severity, only IVIG at 2g/kg + aspirin (without steroids) was prescribed. Soon after starting the treatment, her condition quickly improved, with the CRP and the ESR levels dropped to 5.2mg/L (from 75.5mg/L) and 19mm/hour (from 48mm/hour) in a week, respectively. Serial echocardiogram showed normalized left ventricular contraction after the treatment. Throughout the treatment course, no adverse events were reported. The patient was discharged and followed up every 2 weeks in the first 2 months, and every 6 months thereafter.

COVID-19 vaccine was shown to reduce the risk of MIS-C and related complications

A large case-control study (n=806) in the US found that BNT162b2 was effective in preventing MIS-C and severe complications from MIS-C among children aged 5-18 years who were hospitalized between July 1, 2021 and April 7, 2022.5 Among the 304 MIS-C patients, 280 (92%) were unvaccinated.5 Results found that the incidence of MIS-C was strongly associated with a lower likelihood of vaccination with 2 doses of BNT162b2 messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) vaccine [adjusted odds ratio (aOR)=0.16; 95% CI: 0.10-0.26], including among children aged 5-11 years (aOR=0.22; 95% CI: 0.10-0.52).5 The association remained strong during the Omicron-predominant period (aOR=0.22; 95% CI: 0.11-0.42).5 Of note, 187 MIS-C patients (62%) became critically ill and required ICU admission.5

Conclusion

In summary, MIS-C poses a potential and delayed health threat to children who have just recovered from COVID-19. High awareness of the post-infectious inflammatory condition among parents and clinicians, as well as timely definite diagnosis and intervention are vital for protecting children from MIS-C-associated serious complications and death.