INHALEABILITY FORUM

Reviewing the treatment paradigm in COPD

In an interview with Omnihealth Practice, Professor Michael Dreher reviewed the treatment paradigm for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and the changes in COPD management over the last decades. While discussing the 2023 Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) report, he also expounded on the data of triple therapy of long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) and inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) use in COPD, emphasizing the importance of early diagnosis and treatment.

Individualized management of COPD

COPD is a heterogenous chronic lung disease characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms, including dyspnea, cough and sputum production, as a result of airway and/or alveolar abnormalities, leading to continuous and potentially worsening constriction of the airflow.1 In general, COPD treatment aims to reduce symptoms, prevent future exacerbations, and improve health status.1 The management of COPD should be tailored to each patient starting with diagnosis and initial assessment of the patient’s risk factors and lung function according to the forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1), symptoms, and exacerbation history.1

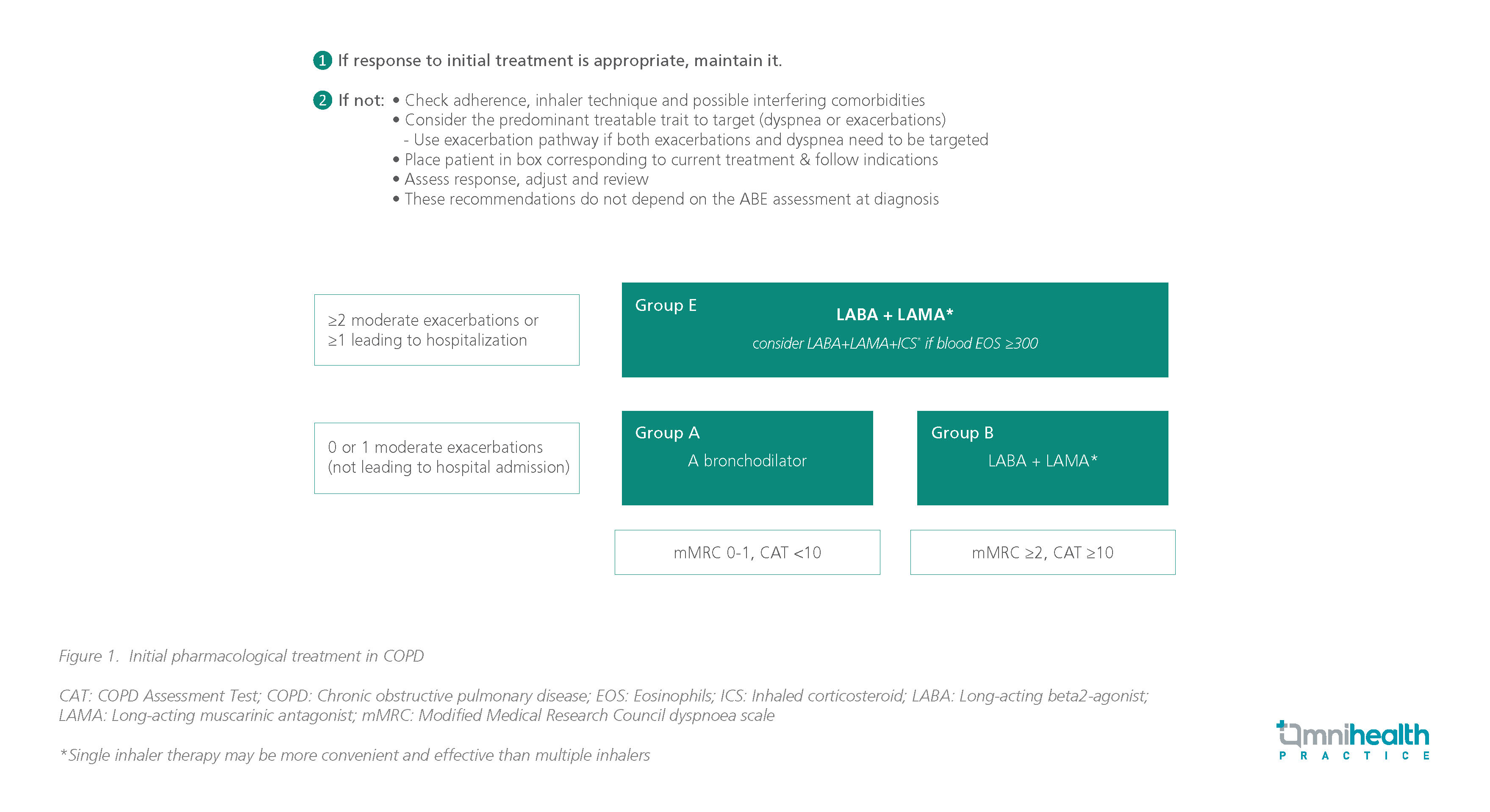

Tracking the predicted FEV1, patients can be classified into 4 classes, with GOLD 1 having the highest FEV1 predicted (≥80%) and GOLD 4 having the lowest FEV1 predicted (<30%), based on the post-bronchodilator value.1 Furthermore, the exacerbation history and symptoms allow for further classification of patients into 3 categories, i.e., group A, B, or E.1 Groups A and B represent patients with 0-1 moderate exacerbations not leading to hospital admissions, and low-risk with group B patients suffering from more daily symptoms.1 Group E includes groups C and D in the previous guideline, representing high-risk patients with ≥2 moderate exacerbations or ≥1 exacerbation leading to hospital admission.1

Currently, initial management includes lifestyle modifications, pharmacotherapy, education on the management plan and inhaler technique, as well as the management of comorbidities.1 Reviewing the patient’s symptoms, mainly dyspnea and exacerbations, is essential and should be followed by an assessment of the patient’s inhaler technique, compliance and non-pharmacological approaches before considering treatment adjustment.1

Updates in COPD management over the last decades

“Over the years, a shift in the COPD treatment paradigm has been underway as newer drugs became available,” Prof. Dreher stated. In the first 40 years (1960s-1990s), drugs approved for COPD patients were only short-acting bronchodilators (SABDs), long-acting bronchodilators (LABDs) and ICS.2 The first LAMA approach, tiotropium, was available in the 2000s.1 In the 2010s, LABA/LAMA fixed-dose combinations were approved and recommended as the basis of COPD treatment in the 2011 GOLD report.2

The latest 2023 GOLD report recommends the use of dual therapy, LABA + LAMA, in all COPD patients as central to symptom management and no longer recommends LABA + ICS in COPD patients.1 Group A patients should be managed with a bronchodilator, while groups B and E patients should be managed with dual bronchodilators (LABA + LAMA).1 ICS may also be considered in addition to dual bronchodilators in group E patients with blood eosinophils count (EOS) ≥300 cells/μL.1 When adopting dual bronchodilators, a single inhaler therapy is preferred due to its superior effectiveness and convenience compared with multiple inhalers (figure 1).1

If the patient’s response to treatment is adequate, treatment should be maintained.1 Otherwise, it is important to assess the patient’s inhaler technique and compliance as well as other comorbidities.1

If the patient is adherent to treatment, treatment should be based on the symptoms, such as dyspnea and exacerbations.1 In case of dyspnea, LABA or LAMA monotherapy or dual therapy is recommended with adequate switching of inhaler device or molecule and treatment escalation.1 In patients with exacerbations alone, LABA or LAMA monotherapy or dual therapy is recommended with escalation to LABA + LAMA if blood EOS <300 cells/μL or triple therapy with LABA + LAMA + ICS if blood EOS ≥300 cells/μL.1 Additionally, roflumilast may be considered in patients with chronic bronchitis and FEV1 <50%, while azithromycin is preferred in previous smokers (figure 2).1 Withdrawing ICS may be considered if pneumonia or other considerable side effects develop.1

Similarly, the 2020 American Thoracic Society (ATS) guidelines also recommend that COPD patients with dyspnea or exercise intolerance should be started on LABA + LAMA over LABA or LAMA monotherapy.3 Dual therapy has been shown to reduce hospital admissions by 11% (p=0.01) and exacerbations by 20% (p=0.002).3

The TONADO trial demonstrated significantly greater improvement in lung function (trough FEV1) and health-related quality of life at 24 weeks in patients receiving tiotropium and olodaterol than monotherapy.4 Additionally, in the OTEMTO trial, the tiotropium and olodaterol combination was associated with clinically significant improvements in dyspnea and quality of life compared with placebo or tiotropium monotherapy, leading to greater improvements in the transition dyspnea index (TDI) focal score and responder rate, as well as the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGQR) total score and responder rate at week 12.5

The IMPACT and ETHOS studies were the largest trials in COPD comparing triple therapy (i.e., LAMA + LABA + ICS) vs. dual therapy (i.e., LABA + LAMA) vs. LABA + ICS.6,7 Comparing umeclidinium and vilanterol, triple therapy with fluticasone, vilanterol and umeclidinium was shown to reduce all-cause mortality (ACM) by 29%.6,7 Similarly, the ETHOS trial showed that triple therapy with 320μg budesonide, formoterol and glycopyrrolate was associated with a 46% reduction in mortality.7 Nevertheless, Prof. Dreher emphasized that we should only think about using triple therapy in a specific patient population, which is symptomatic COPD patients with a significant exacerbation history in the IMPACT and ETHOS trials.1

The GOLD report favors ICS use in patients with a history of hospitalization for exacerbations, moderate exacerbations ≥2 times per year, blood EOS ≥300 cells/μL, and a history of concomitant asthma.1 It may also be considered in patients with 1 moderate exacerbation per year with blood EOS between 100 to 300 cells/μL.1 However, it should not be used in patients with a history of repeated pneumonia events, blood EOS <100 cells/μL, or a history of mycobacterial infections.1

A pooled analysis of 6 phase III/IV trials assessed the time to ACM in 6,000 patients with moderate-to-very-severe COPD with a predominantly low exacerbation risk receiving dual bronchodilators or triple therapy.8 At week 52, there was no difference in survival between the 2 groups (HR=0.93; 95% CI: 0.60-1.43; p=0.742).8

Withdrawal of ICS-containing therapies in COPD

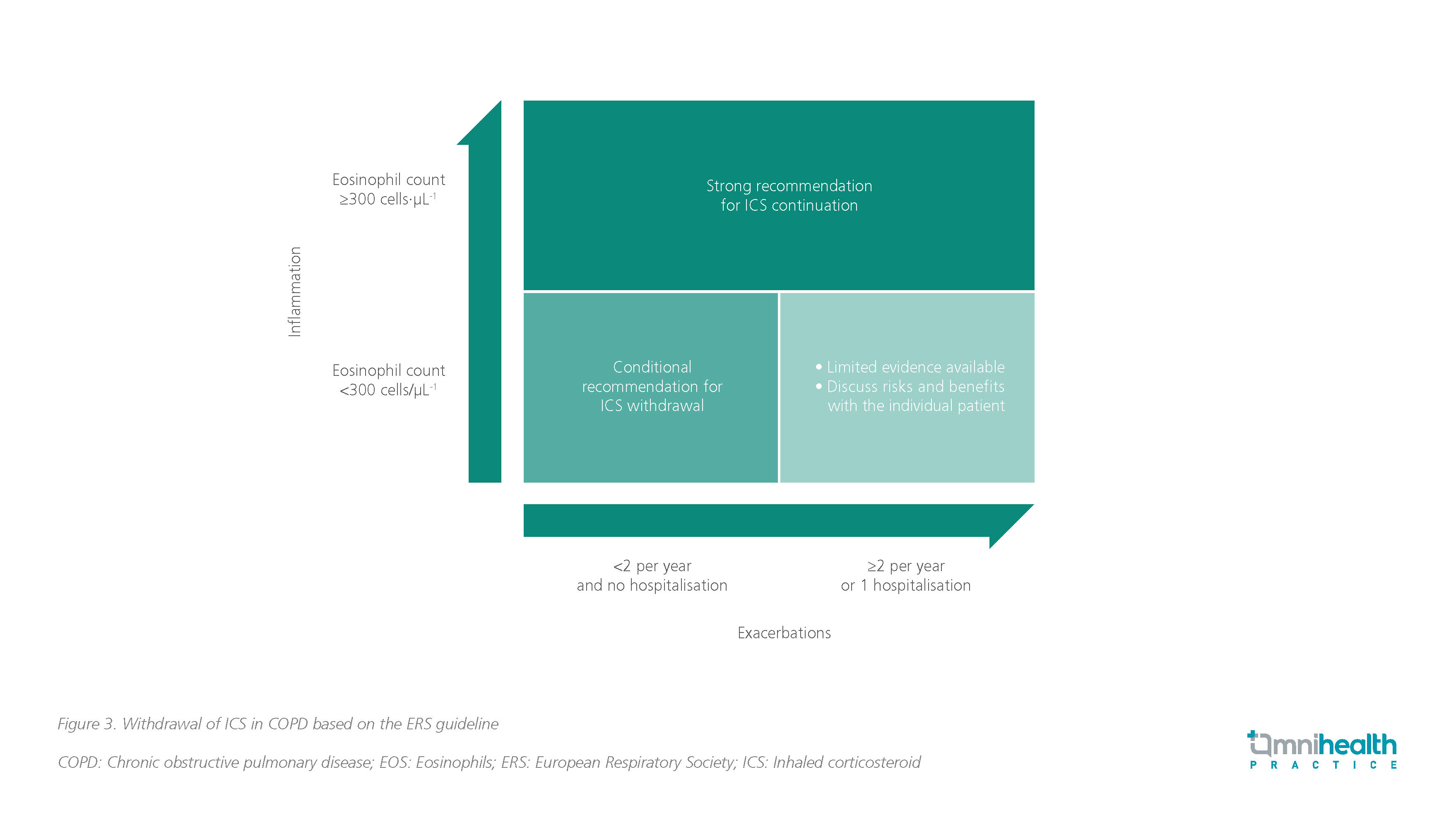

Based on the 2020 European Respiratory Society (ERS) guidelines, ICS should be withdrawn in patients with EOS counts <300cells/μL and <2 exacerbations per year without hospitalization.9 However, ICS should not be withdrawn in patients with blood EOS ≥300cells/μL, with or without a history of frequent exacerbations or hospitalizations.9 Limited evidence on ICS withdrawal is available for patients with EOS <300cells/μL and ≥2 exacerbations per year or 1 hospitalization (figure 3).9

The subgroup analysis of the SUNSET trial supported the above recommendations by indicating that there was no increased risk of exacerbations among patients receiving dual or triple therapy.10 The SUNSET study showed that the de-escalation of COPD patients without frequent exacerbations (≤1 episode of moderate/severe exacerbations during the last year) from long-term triple therapy to LABA + LAMA does not increase the risk of exacerbations.10 The risk of exacerbations after ICS withdrawal appeared to be higher in patients with blood EOS ≥300 cells/μL, suggesting that these patients benefit from triple therapy.10

Early diagnosis and management of COPD

Currently, COPD is diagnosed at the time when irreversible pathological changes occur.11 This is due to several factors, such as the lack of predictive biomarkers, under-recognized clinical symptoms, long period of disease activity associated with no or minimal symptoms, and reliance on spirometry, which is an insensitive diagnostic tool.11 Early diagnosis is essential before irreversible changes occur, allowing for disease interception.11 Lung function loss, assessed as expiratory airflow reduction, occurs mostly during the early stage of COPD (i.e., GOLD 2) than in the late stages (i.e., GOLD 3-4).12

Furthermore, early treatment initiation is associated with slower disease progression and improved health-related quality of life.13 The downward spiral in COPD starts with breathlessness and an increase in inactivity as a result of patient disengagement.14 Prof. Dreher stressed that “We want to prevent patients from going down this spiral and therefore, we should think about starting early in the disease phase.”

A post hoc analysis of COPD patients at different disease stages showed that using dual therapy of tiotropium and olodaterol over monotherapy bronchodilators allows for greater improvement in lung function, irrespective of prior LAMA or LABA maintenance therapy.15 The improvements from baseline in lung function were greater in patients with less severe disease, supporting the use of combination bronchodilation earlier in the course of COPD.15 Hence, Prof. Dreher claimed that starting bronchodilators earlier in the disease phase significantly brings about greater improvements in lung function.

Conclusion

COPD treatment has drastically improved over the last decades to include LABA + LAMA combination as the standard of care in COPD patients with dyspnea. A minority of patients benefiting from triple therapy of LABA + LAMA + ICS are mainly those with an exacerbation history and elevated blood EOS.

Early diagnosis is essential, and that treatment should be started early in the disease phase for greater benefits. Also, it is important to provide adequate training on inhaler use to patients, as well as assess inhaler technique frequently to ensure the effectiveness of the treatment.