CONFERENCE UPDATE: ASH 2022

ASH guidelines and the implementation strategies for the prevention of cancer-associated VTE

In the ASH Annual Meeting& Exposition 2022, Dr. Marc Carrier from the University of Ottawa, Canada, and Dr. Katy Toale from the Anderson Cancer Center, the United States, presented the implementation of risk assessment model and consideration for thromboprophylaxis in ambulatory cancer patients who are receiving chemotherapy, as well as the strategies of optimizing the implementation of ASH guidelines for the treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism (VTE).1,2

The odds ratio of developing VTE in persons with cancer increases 4-fold as compared with the general population, and 6.5-fold if chemotherapy or targeted therapy is initiated.1 A study using a Danish registry of 500,000 cancer patients found that the 6-month risk of VTE was 12-fold greater in cancer patients than in the general population, and it was 23-fold higher in those receiving chemotherapy or targeted treatment.1 This study also found that the 12-month incidence of cancer-associated thrombosis increased from 1% in 1997 to 3.4% in 2017, and was associated with significant morbidity and mortality.1 In general, when compared with patients without cancer, therapeutic anticoagulation is associated with a greater incidence of recurrent VTE or major bleeding.1 Though VTE can occur at various stages after a cancer diagnosis, the majority of cases involve ambulatory patients receiving chemotherapy, where up to 80% of clots are recorded.1

Many studies have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of primary thromboprophylaxis in ambulatory cancer patients receiving chemotherapy, often with low molecular weight heparin (LMWH).1 A review, which evaluated patients initiating chemotherapy who were given a prophylactic dose of LMWH, or placebo or observational, showed that patients receiving thromboprophylaxis had a lower risk of symptomatic VTE [2.8% vs. 5.2%; rate ratio (RR)=0.53; 95% CI: 0.38-0.75].1 The risk-benefit analysis supported the use of thromboprophylaxis, since the number needed to treat (NNT) was 42 and the number needed to harm (NNH) was 250 in chemotherapy patients.1 However, clinicians have a higher threshold for cancer patients, thus discussion of thromboprophylaxis only focuses on very high-risk patients.1 The risk assessment models for identifying high-risk populations include the Khorana risk score, which is the most common index and has been validated in most settings.1 The Khorana risk score is calculated based on different risk factors, including tumor type, complete blood count (CBC) and body mass index (BMI). If the score is 0 (low risk), the risk of VTE at 6 months is 1.5%; if the score is 1-2 (intermediate risk), the risk is 3.8%-9.6%; and if the score is ≥3 (high risk), the risk is 17.7%.1

A meta-analysis evaluating the efficacy of thromboprophylaxis in patients stratified as intermediate to high risk using the Khorana risk score showed that thromboprophylaxis successfully lowered VTE risk in patients with an intermediate to high Khorana risk score.1 This demonstrated that if risk assessment models are used to stratify patients at higher risk, then the NNT is decreased to 25 and the NNH is increased to 1,000, favoring the use of thromboprophylaxis.1

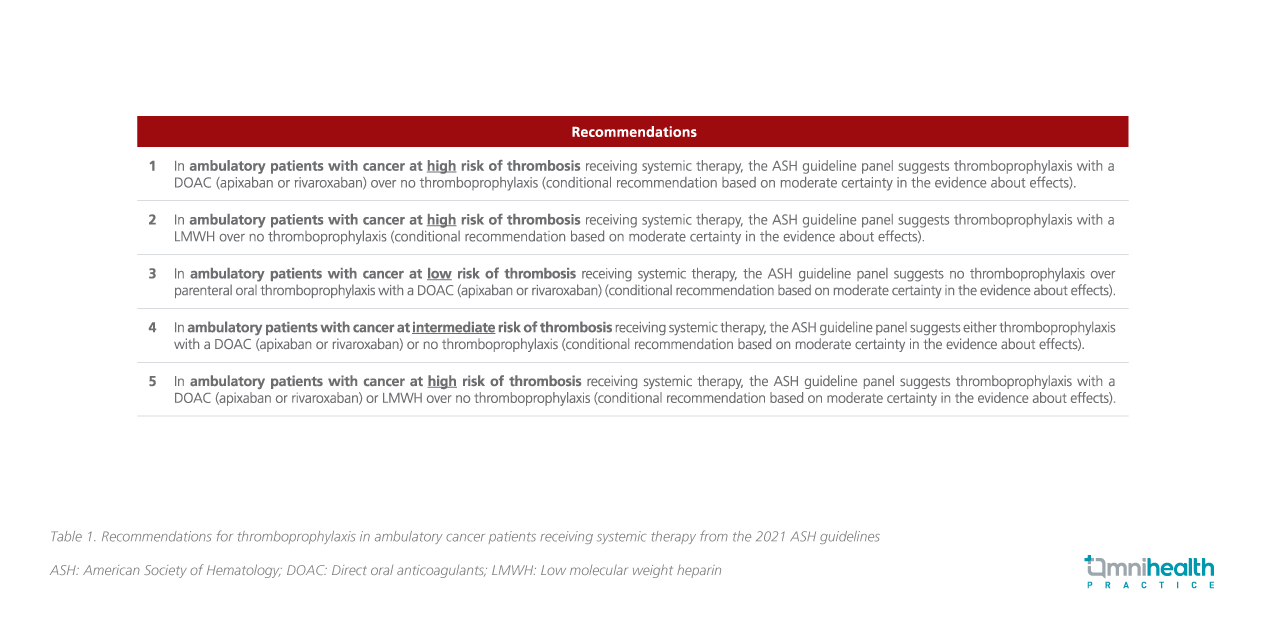

The 2021 ASH guidelines for thromboprophylaxis in ambulatory cancer patients receiving systemic therapy are as follows (table 1):

Dr. Carrier said it is important for clinicians to keep in mind that the classification of patients as low-, moderate- or high-risk for VTE should be based on a validated score (i.e., the Khorana risk score) and complemented by clinical judgment and experience.¹ Besides, thromboprophylaxis should be used with caution in those with high risk of bleeding in high-risk patients for thrombosis.1

Following Dr. Carrier's presentation, Dr. Toale shared how her institution optimized the implementation of the ASH guidelines for treating cancer-associated VTE in an accurate manner, and mentioned about 2 systems for tracking the first instance of VTE in cancer patients.2 The first system identifies patients based on hospital billing code for deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), superficial vein thrombosis (SVT), etc.1 Additionally, the patients must have a prescription for anticoagulant medicine (7 days prior to the code or 30 days after).2 Patients with code from a previous history of VTE are excluded. Furthermore, patients with active cancer on the problem list and encountered within the past 2 years are defined as “denominator”.2 However, since this system does not capture all incidences of VTE, another system using natural language processing (NLP) to extract data from radiology reports is employed.2 This NLP algorithm is extremely sensitive, scanning through thousands of radiological records for cancer patients with VTE using keywords.2

As a quality improvement project, an online clinical decision support tool is created to offer exhaustive patient information, including not only anticoagulant or antiplatelet use and laboratory reports, but also algorithms for transitioning anticoagulants and peri-op management.2 The verifying pharmacists can get access to the same data to confirm the dose and transition.2 Another online tool called the Best Practice Advisory (BPA) alert is created to alert all providers of “high risk of bleeding” if any contraindications to anticoagulants are found, as earlier this information was hidden in charts and not readily viewable in the early stage.2

To prevent the risk of bleeding and increase the nurses’ awareness of safe administration of anticoagulants if platelet counts drop, a flowsheet containing the latest platelet count is prepared, which requires the nurses to document the platelet count prior to every administration.2 To monitor the improvement, every single anticoagulant administration is noted and non-compliant administrations are recorded each month.2 It was found that after using the flowsheet for documenting platelets, the instance of non-compliant drug administration dropped significantly.2

To evaluate the short-term therapy of cancer-associated thrombosis, a few high-risk patient populations were chosen to study the effect of treatment choices on outcomes via retrospective studies.2 Lastly, educating discharged patients on safe anticoagulation use should be advocated, including self-injection technique, in order to facilitate thromboprophylaxis continuation after discharge and to prevent complications.2