EXPERT INSIGHT

Eradicating hepatitis C with modern approaches

Hepatitis C is an infectious liver disease caused by the blood-borne hepatitis C virus (HCV).1 About 70% of patients infected with HCV will develop chronic hepatitis which may lead to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).2 In Hong Kong, patients are mostly infected through blood or blood products transfusion prior to the introduction of anti-HCV screening to the blood transfusion service in 1991.3 In a recent interview with Omnihealth Practice, Dr. Loo, Ching-Kong, Specialist in Gastroenterology and Hepatology, shared his insights on the local management strategies of hepatitis C.

Global and local overview of hepatitis C

In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 0.5-1.0% of the global population are infected with HCV, leading to approximately 399,000 deaths mostly due to cirrhosis and HCC.1 In mainland China and Taiwan, large national seroepidemiological studies revealed an overall HCV prevalence of 3-4%.4 Compared with both global and Asian averages, Hong Kong has a relatively low HCV prevalence of 0.3%.2,4 However, more than 60% of HCV infections in Hong Kong can be attributed to injection drug use, which is much higher than the 23% observed worldwide.1,2

While around 30% of HCV-infected patients can spontaneously clear the virus within 6 months of infection, the remaining 70% can experience HCV-related chronic hepatitis characterized by a chronic HCV carrier state for an average of 10-18 years.1,5 In this state, 27% and 25% of patients can develop cirrhosis and HCC, respectively, as late sequelae of chronic hepatitis.5,6 Notably, these patients are at 15-30% risk of developing cirrhosis within 20 years and 17-24% cumulative risk of developing HCC in their lifetime (aged 30 to 75).1,7

In those who experience HCV-related acute hepatitis, which usually occurs within 6-12 weeks of infection with symptoms such as fever, fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, upper abdominal discomfort, dark urine, grey-colored feces, joint pain, and jaundice, their condition may be indistinguishable from hepatitis caused by other factors.1,2 Moreover, approximately 80% of newly acquired hepatitis C cases are asymptomatic and anicteric, and the infected patient can remain symptom-free until decades later when signs and symptoms secondary to serious liver damage manifest.1,2

Monitoring strategies for hepatitis C in Hong Kong

Since new HCV infections are mostly asymptomatic, the diagnosis of hepatitis C is usually delayed until serious sequelae appear with observable secondary symptoms.1 Fortunately, public education and an improved healthcare system in Hong Kong have helped identify many asymptomatic high-risk patients during medical check-ups.3 As such, a significant proportion of chronic hepatitis C patients in Hong Kong, such as the high-risk adult patients with thalassemia and hemophilia, were infected through repeated blood or blood product transfusion, prior to the launch of the mandatory anti-HCV testing for all blood donors that was implemented by the Hong Kong Red Cross Blood Transfusion Service in 1991.3,8

To help closely monitor the local prevalence of hepatitis C, the Hospital Authority had promoted anti-HCV check-ups since 1998 for those who have received blood transfusion before the implementation of the mandatory blood donor screening program.3 In addition, the Hospital Authority also launched multiple public awareness programs and encouraged individuals at risk of HCV infection to partake in routine anti-HCV testing.3,8 However, despite the development of various monitoring programs, gaps between identifying asymptomatic patients who are unaware of their infection status and educating infected patients on the availability of effective medical treatment still persist.9 As reported in an epidemiological study using data retrieved from the Hong Kong HCV Registry, the estimated territorywide diagnosis rate was at 51% while the treatment coverage rate was only around 12%.10 Where territory-wide screening program may improve the rate of early HCV diagnosis, the local prevalence rate of HCV infection is too low for this strategy to be considered cost-effective.10 Therefore, targeted screening of the population at-risk, including people with injection drug use, received blood transfusion before 1990s, high-risk sexual behavior, and a family history of HCV infection, should be considered to ensure an early diagnosis and timely intervention to those predisposed to HCV infection.10

Populations with higher risk of HCV mortality require routine test for better disease control

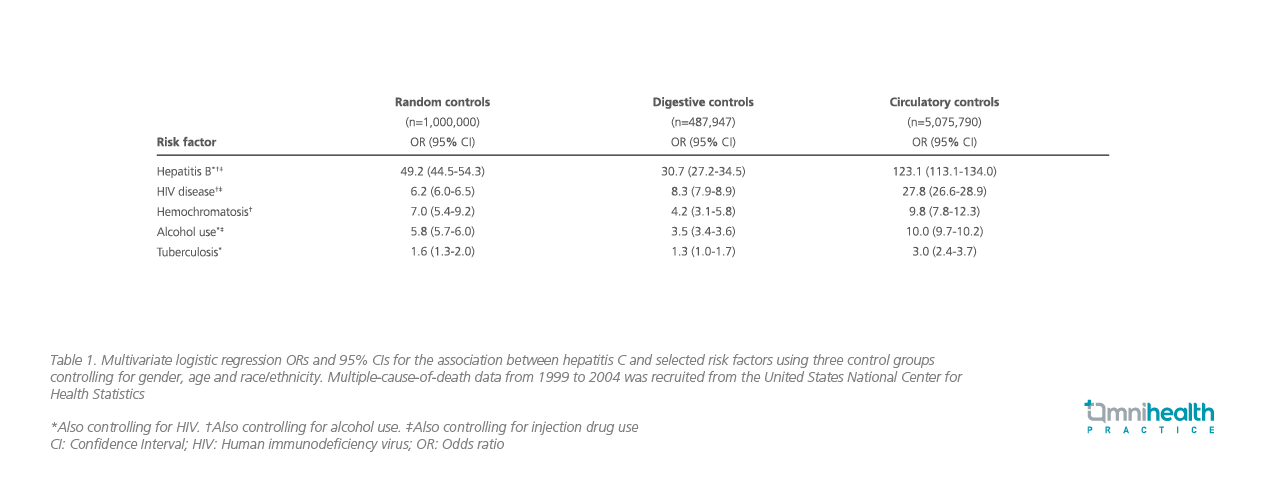

Where routine check-ups can be implemented for patients who are at increased risk of HCV infection, those with higher chance of severe disease and mortality associated with hepatitis C should also be identified. In a case-control study using multiple-cause-of death data from the United States during 1999-2004, 63,189 hepatitis C deaths were analyzed to estimate the association between several prognostic factors and hepatitis C mortality.11 As comparators, the mortality rate was analyzed against control groups of non-hepatitis C mortality (random controls), digestive disease-related non-hepatitis C mortality (digestive controls) and circulatory disease-related non-hepatitis C mortality (circulatory controls).11

The findings stated that hepatitis B (OR=30.7-123.1), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease (OR=6.2-27.8), hemochromatosis (OR=4.2-9.8), and alcohol use (OR=3.5-10.0) are strongly associated with hepatitis C and may have contributed to the increased mortality and clinical course of hepatitis C (Table 1).11 Also, hepatitis B, HIV disease and alcohol use were found common among hepatitis C deaths (6.4%, 10.5%, and 18.2% of case deaths respectively), indicating that early intervention targeting these conditions may be an effective strategy to reduce the population burden of hepatitis C-related deaths and its associated comorbidities.11 Given the association between these factors and the disease prognosis, routine anti-HCV testing targeting these at-risk populations can help identify the mode of HCV transmission within the local community and limit the population burden of hepatitis C infection.11

Pangenotypic direct-acting antiviral is a safe and convenient treatment option for hepatitis C

As chronic hepatitis C is curable, the treatment goal for hepatitis C is often cure as defined by sustained virological response (SVR) which occurs when the blood test shows no detectable HCV ribonucleic acid (RNA) in 12 weeks after treatment completion.1,2 Previously, combination therapy with pegylated interferon (peg-IFN) and ribavirin (RBV) was the treatment of choice that can provide SVR rates of 30-90% depending on the HCV genotype and the stage of liver disease.5,12 Despite this apparent efficacy in SVR, peg-IFN and/or RBV are associated with several side effects including flu-like symptoms, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and depression, and are contraindicated for many patients with hepatitis C.12

In contrast, DAAs are highly effective with a cure rate of well over 90%, better tolerated with minor side effects, do not require injection, has a shorter treatment duration that usually takes around 8-12 weeks, and has a better drug compliance rate.2 While past data suggested that HCV genotypes would affect the response to HCV treatment, the latest DAAs can overcome this constraint as they are pangenotypic, providing similar rates of cure across different HCV genotypes.13 In particular, patients infected with genotype 1, especially subtype 1b which is the most prevalent HCV genotype among Hong Kong blood donors, have a greater risk of cirrhosis and HCC than other genotypes.3 Genotype 3 is uniquely associated with an increase in hepatic steatosis, which is believed to be related to direct effects on lipid metabolism in liver cells.14 Regardless of the genotypes that complicate the treatment, the pangenotypic nature of DAAs enables consistent viral suppression among all HCV genotypes where high SVR rates of >90% were observed in patients with HCV genotype 3 and concurrent HBV or HIV infection.13 Even for cases with decompensated cirrhosis and HCV genotype 3 infection, 50-85% of patients achieved SVR with DAAs.13 Given the demonstrated benefit of DAAs, both the WHO and European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) now recommend DAAs as the backbone of treatment for hepatitis C.1,13

Local practice of hepatitis C management

The local treatment strategies for hepatitis C are often affected by the comorbidities and the genotype of HCV infection. At the early stages of hepatitis C, DAAs can be equally given to patients with no progress to cirrhosis or decompensation, or to patients with no concurrent hepatitis B virus or HIV infection regardless of the comorbidities or the genotype of HCV infection. In fact, real-world studies showed that 90-100% of patients with chronic hepatitis C without cirrhosis or with compensated cirrhosis can achieve SVR with DAAs alone.13 At the advanced stages of hepatitis C, however, many would develop HCC that could require liver transplant if no other surgical treatments are considered feasible. That said, for HCC patients who have no cirrhosis or with compensated (Child-Pugh A) cirrhosis and an indication for curative therapy including liver transplantation, their indications for antiviral treatment are similar to those without HCC.13

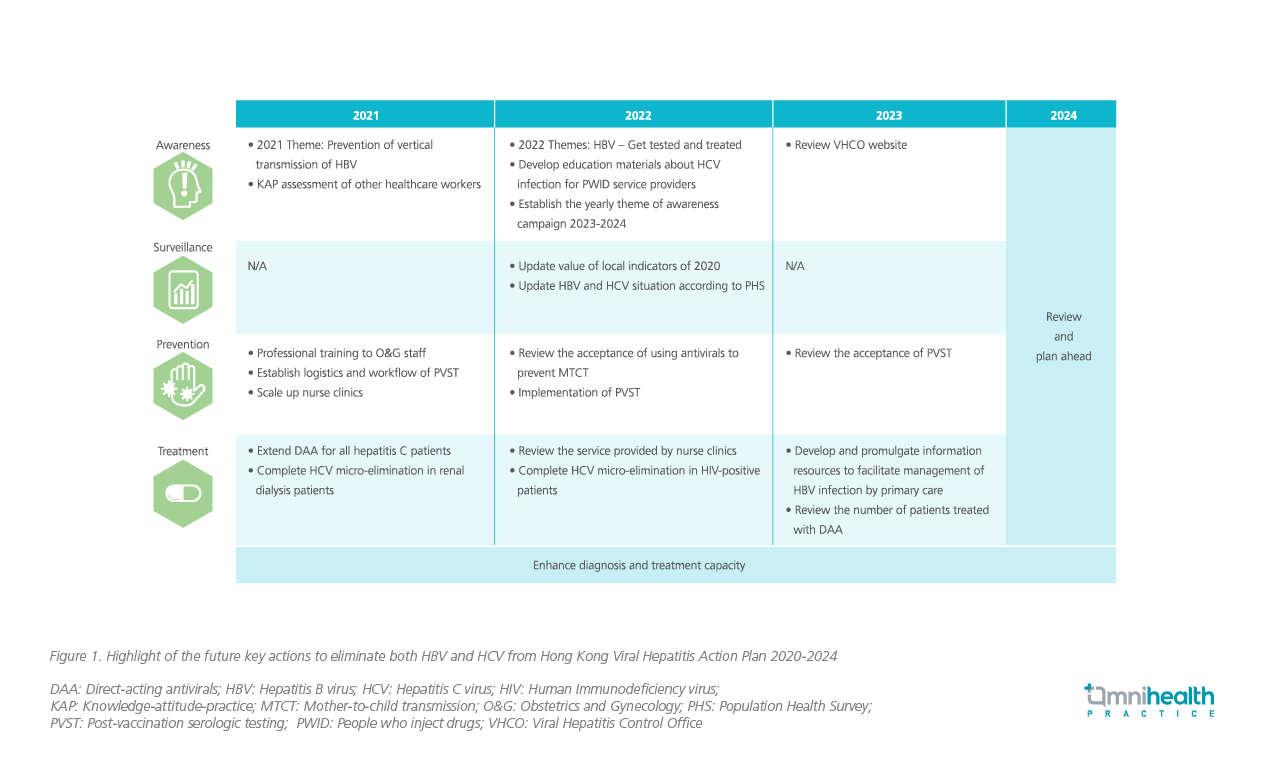

According to the Hong Kong Viral Hepatitis Action Plan 2020-2024, the Hong Kong government aims to extend DAA for all hepatitis C patients and complete HCV micro-elimination in renal dialysis patients by 2021 (Figure 1).9 Through the HCV testing algorithms, blood safety strategies and prompt treatment initiation to HCV patients, local progress in eliminating HCV infection is aligned with the 2030 HCV elimination target set by the WHO.9 Following the plan, local healthcare professionals can take the initiative to recognize and provide prompt interventions to patients predisposed to hepatitis C, prior to the irreversible disease progression.

Of note, when attempting to eradicate the disease in the locality, clinicians should be aware of the few contraindications to HCV treatment with DAA drug combinations.13 For example, treatment regimens comprising HCV protease inhibitors, such as grazoprevir, glecaprevir or voxilaprevir, are contraindicated in patients with decompensated (Child-Pugh B or C) cirrhosis and in patients with previous episodes of decompensation.13 Fortunately, as multiple DAAs are now readily available in the local market, clinicians can quickly adapt to another DAA when contraindications are observed.

Message to physicians and conclusion

In the current pandemic, access of patients to medical care may be compromised for all reasons. While regular management of hepatitis C can be expected to resume after the resolution of COVID-19, clinicians should continue to encourage high-risk patients to maintain routine follow-ups and provide timely intervention with DAAs when needed. Particularly, the current treatment for hepatitis C with pangenotypic DAAs has largely improved in SVR rates, safety and cost-effectiveness when compared with the treatment options available several decades ago. As such, prompt anti-HCV testing, diagnosis and proactive treatment should be provided to patients with possible HCV infection, especially those with otherwise unexplained liver disease or abnormality in liver function testing results.