INDUSTRY ESSENTIALS

Extending endocrine care beyond β-thalassemia major: International consensus guideline in children and adolescents

Thalassemia arises from mutations in the α- or β-globin genes, with 5%-10% of the global population carrying α-thalassemia mutations and at least 40,000 children born with β-thalassemia annually.1 The disease is most prevalent in the Mediterranean, Middle East, Indian subcontinent, China, and Southeast Asia.1 Although advances in transfusion and chelationhave improved survival in patients with β-thalassemia major—and in some with β-thalassemia intermedia and α-thalassemia hemoglobin H disease (HbH) disease—individuals across this spectrum remain at considerable risk of endocrine complications.1

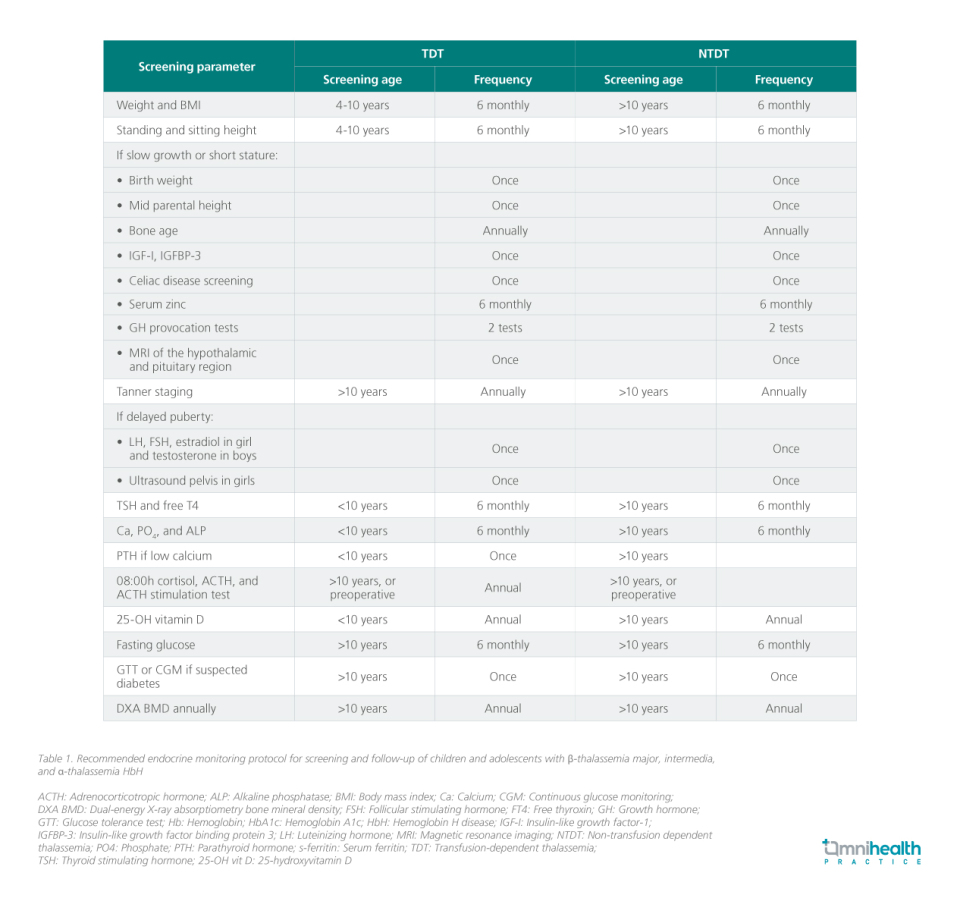

Earlier guidelines on endocrine care in thalassemia focused mainly on β-thalassemia major, leaving gaps in management strategies for patients with β-thalassemia intermedia and α-thalassemia.1 To address this, an international panel of 14 experts representing eight pediatric endocrine societies convened to review the evidence and develop best practice recommendations.1 Using a Delphi process, 43 consensus statements were finalized, covering screening and management of endocrine dysfunction across all forms of thalassemia in children and adolescents.1

In an interview with Omnihealth Practice, Professor Dr. Muhammad Yazid Jalaludin, one of the co-authors of the international consensus guideline, discussed the challenges of endocrine complications in thalassemia and the importance of comprehensive care for children and adolescents.

Q1: Why was it important for the consensus to update recommendations on endocrine complications in thalassemia?

Prof. Yazid: Thalassemia is highly prevalent in Southeast Asia, and management has traditionally focused on β-thalassemia major. However, endocrine complications are driven not just by genotype but by transfusion dependence (and complications of iron overload). Patients with β-thalassemia major typically begin transfusions within the first year of life, while other TDT subtypes may only require them later in childhood. Regardless of subtype, once a patient becomes TDT—especially after significant transfusion burden or when ferritin exceeds 1,000ng/mL—they should be screened for endocrine complications.

Unfortunately, screening practices are inconsistent, particularly in non-β-thalassemia major TDT. This was a major gap the guideline sought to address, as early recognition and timely treatment may restore gland function.

Q2: Which endocrine complications have the greatest impact on patients, and how should clinicians approach monitoring and management?

Prof. Yazid: While diabetes is a serious late-stage complication, growth and pubertal disorders have the greatest long-term impact on quality of life. Hypogonadism and delayed puberty affect bone health, fertility, and psychosocial well-being, while growth failure carries lifelong consequences. Most hormone deficiencies are treatable with replacement therapy, but GH deficiency remains under-recognized.

In Malaysia, GH stimulation testing is rarely performed, as short stature is often attributed to thalassemia itself. Yet, growth in thalassemia is multifactorial—chronic anemia, nutritional deficiencies, iron overload impairing insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) liver production, and chelator-related skeletal effects all play a role. GH deficiency should therefore be considered a diagnosis of exclusion. When indicated, GH therapy is typically continued until bone age reaches ~14 years in girls and ~16 years in boys, reflecting epiphyseal closure rather than chronological age.

Hypogonadism affects up to 50% of patients with β-thalassemia major and is often the result of iron deposition in the pituitary, leading to hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (HH). Hypogonadism is characterized by the absence of testicular enlargement (>4mL) in boys and the absence of breast development in girls by age 16 years.

Q3: What are the key challenges in implementing these recommendations, and what steps can improve care going forward?

Prof. Yazid: The main challenges are resource limitations and delayed diagnosis. Missing the treatment window, particularly for growth, can mean irreversible outcomes. Access to endocrine expertise is also uneven, and transition to adult services is often unstructured, with adolescents sometimes referred prematurely.

To improve care, we need standardized workflows embedded in routine thalassemia management: when to screen, which tests to order, and how to act on results. Even simple interventions, like diagnosing hypothyroidism or treating hypogonadism, can dramatically improve patients’ energy, growth, and quality of life. A checklist-based approach, ideally delivered within multidisciplinary transfusion clinics, could help ensure no complication is overlooked and facilitate a smoother transition into adulthood.