EXPERT INSIGHT

Cracks in the network: How vascular disease shapes the dementia burden

Dementia affects over 57 million people globally, with numbers projected to triple by 2050 due to population aging.1 While Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dominates clinical focus and public attention, vascular dementia (VaD), the second most common subtype, poses its own set of diagnostic challenges, and a compelling opportunity for prevention through effective vascular risk management and multidisciplinary care.2,3 In a recent interview with Omnihealth Practice, Dr. Mohamad Imran Idris, Consultant Neurologist from the Sunway Medical Centre in Malaysia, shared insights into the evolving landscape of VaD, from disease pathophysiology, diagnostic complexities, to emerging advances in imaging and the often-underestimated value of integrated care approaches.

Understanding the vascular roots: How VCI progresses to VaD

Vascular cognitive impairment (VCI) refers to a broad spectrum of cognitive disorders caused by cerebrovascular pathology, ranging from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to severe dementia.1 Two major contributors to VCI are poststroke cognitive impairment and cerebral small vessel disease (SVD)-related cognitive decline, both of which frequently overlap with neurodegenerative conditions such as AD, making diagnosis and management more complex.1,2

Poststroke cognitive impairment is particularly common, with 38% experiencing MCI and nearly 1 in 5 progressing to dementia.1 Risk is strongly influenced by lesion characteristics, especially when “strategic” brain regions such as the left frontotemporal lobe, left thalamus, or right parietal lobe are affected.1 Equally important is the brain’s resilience, shaped by factors such as pre-existing neurodegenerative conditions (e.g. AD and SVD), cognitive reserve (e.g. education and intellectual engagement), and overall health status (e.g. age, presence of diabetes, and other cardiovascular risk factors).1

In contrast, SVD causes slow, cumulative damage, even in the absence of clinical strokes.1 It affects small perforating arterioles, venules, and capillaries of the neurovascular unit, leading to endothelial dysfunction, vessel rupture or narrowing, disruption of the blood-brain barrier, neuroinflammation, and impaired clearance systems like the glymphatic pathway.1 These processes gradually erode brain integrity and precipitate cognitive decline.1 “There is no single hallmark symptom for VaD,” explained Dr. Idris. “While executive dysfunction and decreased processing speed are common, the range of cognitive impairment in VaD can also include deficits in short- and long-term memory.”

At the severe end of the spectrum lies VaD, which is functionally impairing and often irreversible.1,3 VaD accounts for 15%-20% of dementia cases in high-income countries and up to 30% in parts of Asia and low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).4 While some cases of VaD may follow a single strategic infarct and manifest abruptly, the condition more often reflects chronic, cumulative damage to the brain’s vascular network, particularly in the setting of SVD.1,2

Bridging gaps in diagnosing VaD: Challenges and emerging tools

Accurate diagnosis of VaD remains challenging due to the lack of definitive biomarkers and the overlapping features with other dementia subtypes.2 Current diagnostic criteria emphasize the presence of cognitive impairment, evidence of cerebrovascular disease (e.g. infarcts or white matter changes on neuroimaging), and a temporal relationship between the two.1 “However, in cases involving SVD, symptoms often develop slowly, making the temporal connection less obvious.” Dr. Idris noted.

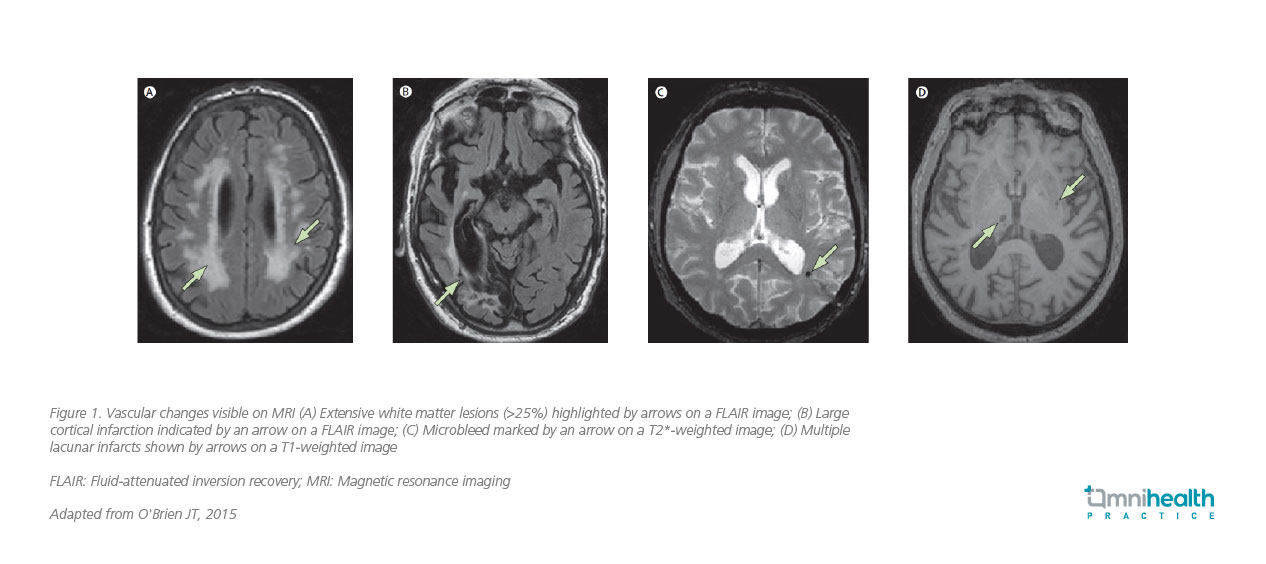

Hence, diagnosing VaD requires a multifaceted approach.2 Clinicians typically begin with a thorough history and physical examination, looking for signs of stroke or other neurological deficits.6 Neuropsychological assessments, such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) or Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), are used to evaluate cognitive function.6 Neuroimaging remains central to diagnostic workup.7 The United Kingdom (UK) National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends structural brain imaging in all cases of suspected dementia, with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) preferred when a vascular etiology is suspected.7 MRI can detect features suggestive of VCI, including strategic infarcts, lacunes, white matter hyperintensities, cerebral microbleeds, enlarged perivascular spaces (PVS), and brain atrophy (figure 1).7 It can visualize recent small infarcts for several weeks after onset, supporting identification of temporal associations between vascular injury and cognitive decline.7

Advanced imaging techniques such as diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) tractography and functional MRI are beginning to shed light on the structural and functional disruptions underlying VCI.7,8 DTI, in particular, offers detailed characterization of white matter microstructure by measuring the degree of anisotropy and the magnitude and orientation of water molecule diffusion.7 Tractography derived from DTI enables visualization of white matter tracts, revealing potential disruptions associated with vascular injury and offering a more sensitive assessment of microstructural damage than conventional imaging.7

“Many of these technologies remain largely confined to research settings,” Dr. Idris acknowledged. “Their specificity and cost-effectiveness for real-world clinical use, especially in developing nations, are yet to be determined. Nonetheless, they represent exciting frontiers.”

Even with advanced imaging, the diagnostic process is not always straightforward.2 “There’s significant overlap, especially in the elderly, where mixed dementia is increasingly common.” Advanced tools, such as amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) imaging and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers (e.g. Aβ42, total tau, and phosphorylated tau) are valuable for detecting underlying AD’s pathology, but these remain cost-prohibitive and unavailable in most public healthcare systems.9

“There’s a pressing need for blood-based biomarkers that are affordable, minimally invasive, and scalable,” he emphasized. “While progress has been made, the tools are currently validated only for AD. We lack equivalent assays for VaD or frontotemporal dementia.” Despite this, Dr. Idris expressed optimism about the potential of blood-based biomarkers for dementia in the future.

The overlooked opportunity: Prevention through risk factor management

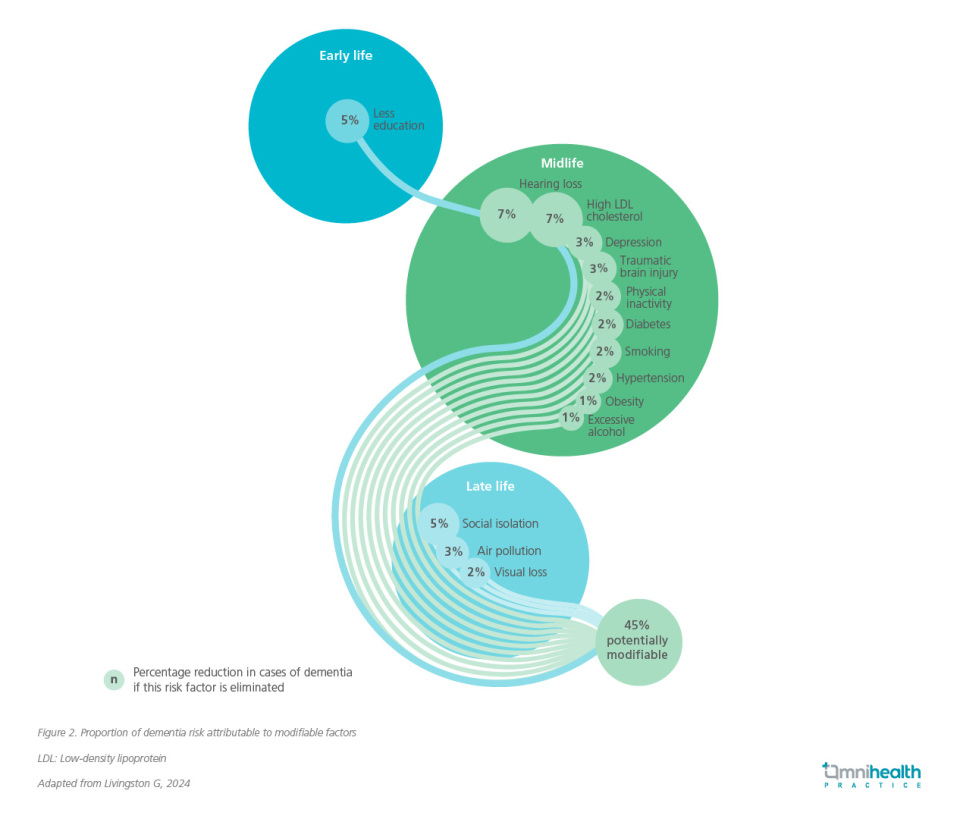

A growing body of evidence highlights the significant association between vascular risk factors and all-cause dementia, including vascular dementia.1 The 2024 Lancet Commission reaffirmed the critical role of modifiable risk factors across the life course, identifying 14 key contributors, including hypertension, diabetes, obesity, physical inactivity, hearing and vision loss, low educational attainment, social isolation, and air pollution.10

The risk of dementia depends not only on the presence of individual risk factors but also on their cumulative effect, timing, and duration of exposure.10 Midlife appears to be a particularly critical window, as interventions during this stage—such as blood pressure and lipid control, diabetes management, and smoking cessation—are associated with reduced dementia risk later in life.10 These factors often cluster and are more prevalent in LMICs, largely due to suboptimal control of cardiovascular disease (CVD).1 While nearly half of all dementia cases could be preventable through coordinated, multilevel interventions targeting these modifiable factors, addressing these risks is thus a global health imperative, particularly in LMICs, where the impact of prevention could be most profound.10

Proactive dementia prevention—through lifestyle modification, pharmacologic control of risk factors, and promotion of social and cognitive engagement—may offer the most effective means of reducing the burden of VaD (figure 2).2,10 Moreover, comprehensive post-stroke management, including physical rehabilitation and cognitive stimulation, may help slow cognitive decline in affected individuals.11

“Of all the risk factors, social isolation is among the most concerning,” Dr. Idris cautioned. “It’s not just about being physically alone—it's about emotional and social disconnection. You can be surrounded by people yet still miss real connection, especially when absorbed in a screen.” He reflected on how the COVID-19 pandemic had accelerated cognitive decline in many patients, attributing it in part to the loss of meaningful social engagement.

Multidisciplinary models of care

Effective VaD management requires a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach involving neurologists, geriatricians, psychiatrists, physiotherapists, and other healthcare professionals.3 Importantly, caregiver involvement and support systems play an indispensable role.3 Dementia care can be emotionally and financially exhausting for families, especially in resource-limited settings where formal care infrastructure is lacking.12 Education and respite services for caregivers are essential to sustaining home-based care and preventing burnout.3

In many primary care settings, cognitive symptoms in older adults are often overlooked, and routine cognitive screening is seldom performed.12 Some clinicians may hesitate to pursue diagnostic workups due to perceived futility, particularly given the limited pharmacological options and cost barriers.12 However, this mindset overlooks the substantial benefits of early identification. Even without curative treatments, early diagnosis allows for risk factor management, advanced care planning, and timely support services.10 It is essential to educate both the public and healthcare providers on the value of early recognition and multidisciplinary care.12 “Building such coordinated networks of care is particularly important in low-resource settings, where support systems may be fragmented,” said Dr. Idris.

Towards a new paradigm in dementia care

While there are currently no disease-modifying therapies specifically for VaD, some clinicians may prescribe donepezil (cholinesterase inhibitors) or memantine (an NMDA receptor antagonist), especially if mixed pathology is suspected. However, their efficacy in pure VaD remains limited and inconsistent.6 As the field moves forward, there is also growing interest in applying artificial intelligence (AI) to dementia therapy.13 One example of this is using generative AI to recreate scenes from a patient’s past in order to carry out what is known as reminiscence therapy, an approach that has the potential for improving well-being and reducing depressive symptoms.13 “I do believe we’re just at the beginning of what could be a major transformation in dementia care,” shared Dr. Idris.

Conclusion

In conclusion, VaD represents a significant yet underexplored domain within the dementia spectrum.1 As dementia care evolves, prioritizing VaD—through advances in neuroimaging, accessible molecular biomarkers, and, critically, a proactive multidisciplinary approach to early vascular risk management—will be key to reducing cognitive decline and improving quality of life for patients and their families.1,2,7,8,10