FEATURES

Ruxolitinib in high-risk PV: Addressing unmet needs and delivering durable clinical benefit

Polycythemia vera (PV) is a complex and chronic hematologic disorder.1 Despite established treatment protocols, many patients experience persistent symptoms and inadequate disease control, particularly when resistant or intolerant to first-line therapies.2 In a series of recent guest lectures in Hong Kong, Professor Mary Frances McMullin from Queen’s University Belfast in Northern Ireland explored the unmet needs of PV patients in the post-hydroxyurea (HU) setting. She emphasized the importance of healthcare professionals remaining vigilant to the clinical need for optimal treatment options when intolerance or resistance to HU arises. By examining clinical trial data, real-world evidence, and patient outcomes, Prof. McMullin highlighted the therapeutic potential of ruxolitinib in delivering durable clinical benefits and improving quality of life for individuals living with PV.

Understanding PV: A chronic challenge

PV is a chronic myeloproliferative neoplasm characterized by clonal erythrocytosis, elevated hematocrit, and a markedly increased risk of thrombotic events.1 Patients frequently suffer from debilitating symptoms such as fatigue, pruritus, headaches, and splenomegaly.1 The primary goals in managing PV include reducing thrombosis risk, and other long-term clinical endpoints include controlling blood counts, alleviating symptoms, and preventing disease progression.1,2 For high-risk patients—typically those over 60 years of age or with a history of thrombosis—standard treatment involves cytoreductive therapy alongside low-dose aspirin and phlebotomy to maintain hematocrit levels below 45%.1 HU has long been the first-line cytoreductive agent, but a significant portion of patients may develop resistance or intolerance, necessitating alternative therapies.1,3 In such cases, ruxolitinib, a JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor, has been shown to be an effective second-line option, offering durable survival benefit, hematocrit control, symptom relief, and reduction in JAKV617F allele burden.2

Spotlighting HU-resistance after first-line care

Despite the role of HU as a widely used first-line cytoreductive therapy for high-risk PV, treatment unmet needs persist, and periodic phlebotomy is still required.1 A retrospective observational study analyzing data from a German database of 4 million individuals over 8 years revealed that 43.6% of high-risk PV patients receive no cytoreductive therapy at all.3 Among those treated with HU, more than 63.2% exhibit signs of intolerance or resistance, underscoring the limitations of HU and the urgent need for more effective and better-tolerated therapeutic options.3

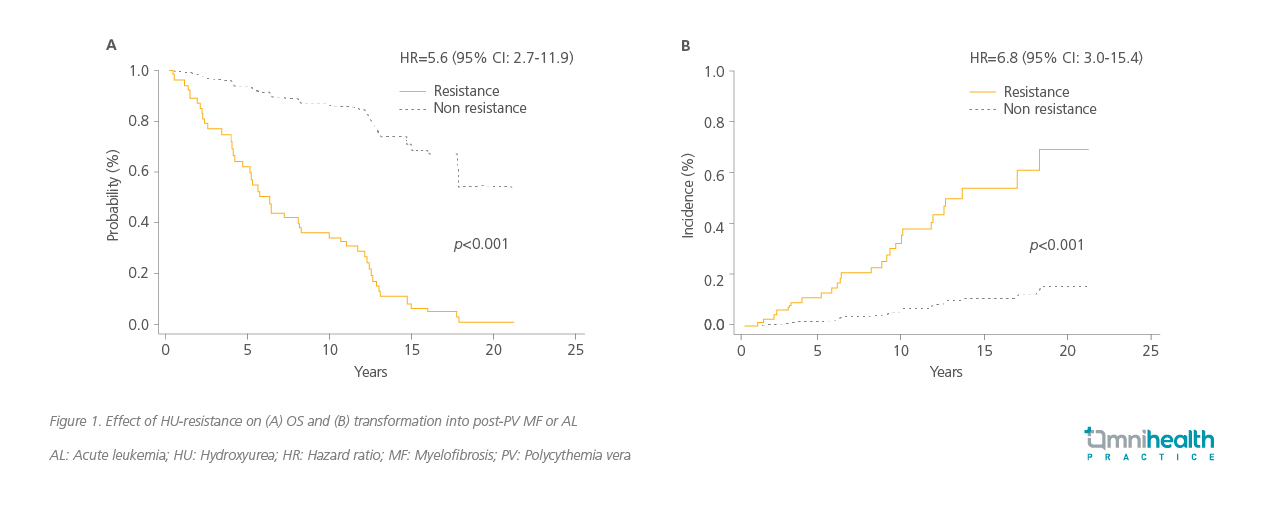

HU resistance in PV significantly worsens patient outcomes.4 In a retrospective observational study conducted in Spain among PV patients treated with HU (n=261), HU-resistant patients were shown to face a 5.6-fold increased risk of death (p<0.001) and a 6.8-fold higher likelihood of disease transformation into myelofibrosis (MF) or acute leukemia (AL) (p<0.001) (figure 1).4

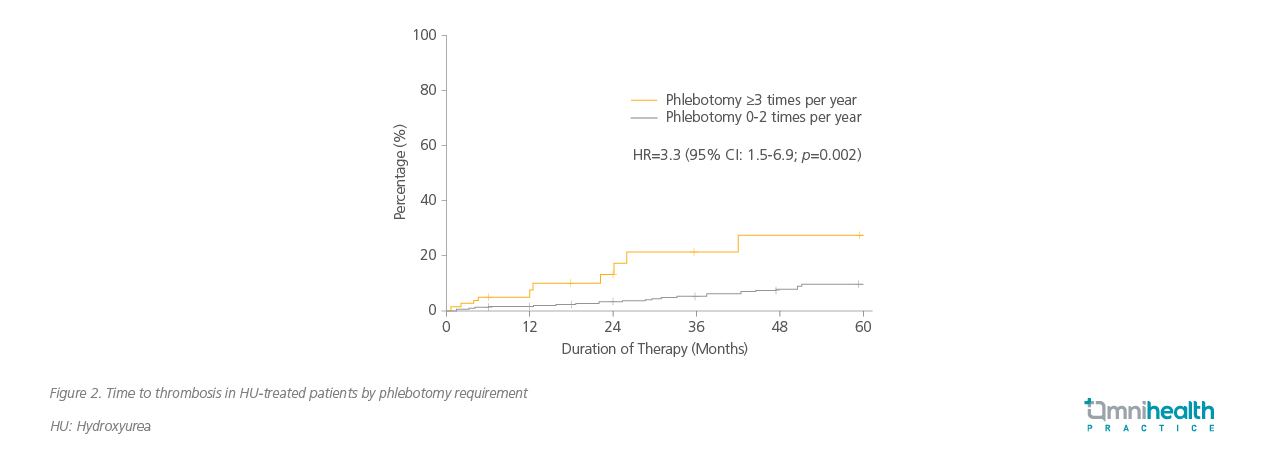

Despite high-dose HU therapy, many patients continue to require phlebotomy, indicating inadequate hematocrit control.5,6 In the RESPONSE and RESPONSE-2 trials, up to 62.4% of HU-intolerant or resistant patients receiving best available therapy (BAT) still required phlebotomy, and 22.7% needed three or more procedures within 28-32 weeks.5,6 The REVEAL study further highlighted the burden of phlebotomy, with patients reporting fatigue, discomfort, and missed work.7 Importantly, frequent phlebotomy— defined as three or more sessions per year—is independently associated with a 3.3-fold increased risk of thrombosis (figure 2).8

Despite high-dose HU therapy, many patients continue to require phlebotomy, indicating inadequate hematocrit control.5,6 In the RESPONSE and RESPONSE-2 trials, up to 62.4% of HU-intolerant or resistant patients receiving best available therapy (BAT) still required phlebotomy, and 22.7% needed three or more procedures within 28-32 weeks.5,6 The REVEAL study further highlighted the burden of phlebotomy, with patients reporting fatigue, discomfort, and missed work.7 Importantly, frequent phlebotomy— defined as three or more sessions per year—is independently associated with a 3.3-fold increased risk of thrombosis (figure 2).8

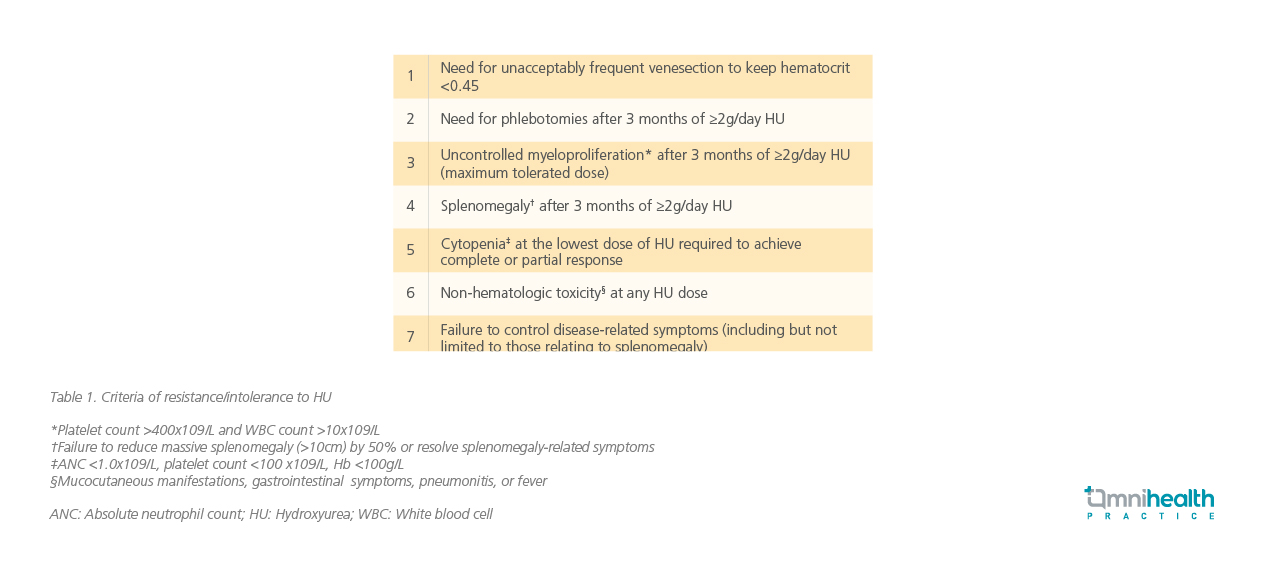

Studies reflected that patients with suboptimal response to HU continue to experience uncontrolled leukocytosis or thrombocytosis, suggesting insufficient suppression of myeloproliferation.9 Furthermore, phlebotomy is still necessary for these patients with suboptimal response to HU representing a lack of urgency to transition away from HU.9 In these patients, higher rates of splenomegaly and high symptom burden correspond to a switch to ruxolitinib in real-world cohorts.9 Prof. McMullin noted that non-hematologic toxicities are also common, including mucocutaneous ulcers, gastrointestinal symptoms, and persistent fatigue, and highlighted that ruxolitinib should be considered for those patients. These findings underscore the limitations of HU and phlebotomy in managing PV and emphasize the need for timely transition to more effective therapies.2 Resistance or intolerance to HU in PV is defined as the following (table 1).10

Ruxolitinib: An established option for HU-resistant/ intolerant PV

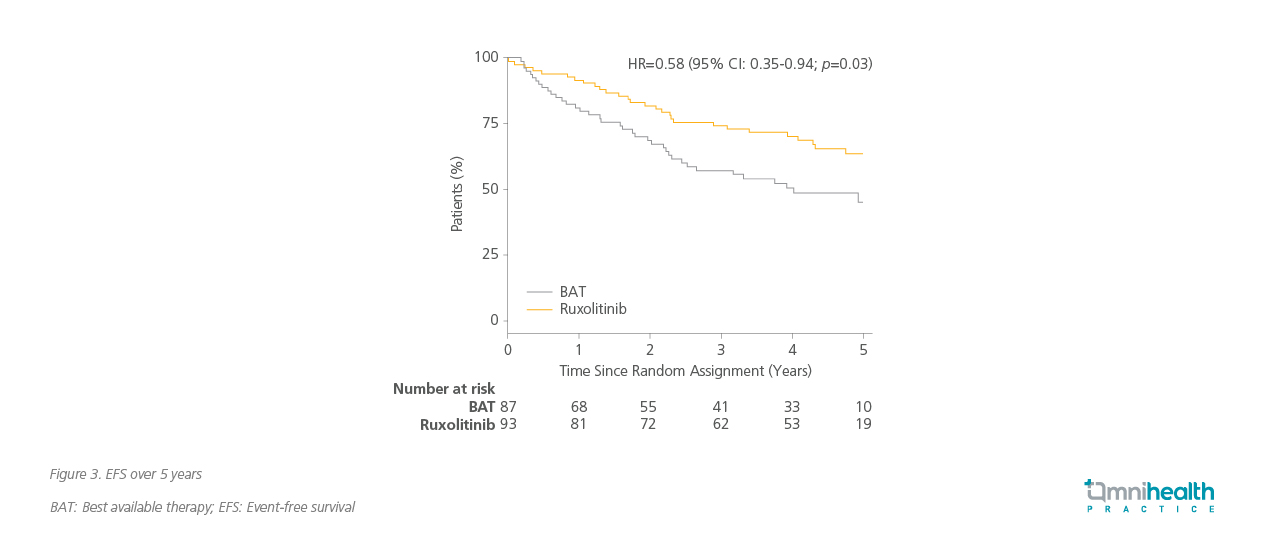

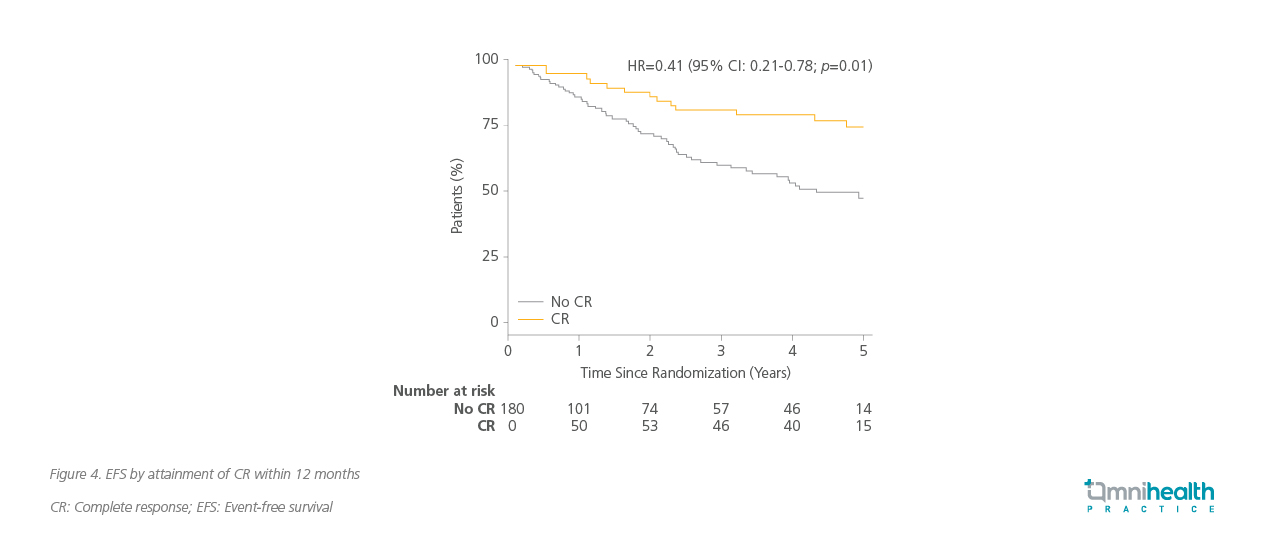

Ruxolitinib is an inhibitor of JAK1/2, key components of the signaling pathways involved in hematopoietic hyperproliferation, and is approved for the treatment of PV in adults who are resistant or intolerant to HU.2,5,6 Building on its mechanism of action and symptomatic benefits, ruxolitinib’s clinical utility was further explored in the MAJIC-PV trial, which directly compared its efficacy to BAT in a high-risk patient population.2 The MAJIC-PV trial was a phase 2, randomized, open-label study designed to compare ruxolitinib with BAT in patients with high-risk PV who were resistant or intolerant to HU.2 The trial evaluated multiple endpoints, including complete response (CR), event-free survival (EFS), symptom burden, and molecular response.2

Within 12 months, 40% of patients treated with ruxolitinib achieved CR, compared to only 23% in the BAT group (odds ratio [OR]=2.12; 90% CI: 1.25-3.60; p=0.02).2 Furthermore, ruxolitinib significantly reduced the risk of losing CR by 62% (HR=0.38; 95% CI: 0.24-0.61; p<0.001), indicating a more durable response, with a 77% risk reduction in discontinuation of first treatment (HR=0.23; 95% CI: 0.14-0.36; p<0.001).2

The benefit of ruxolitinib demonstrated across multiple clinical endpoints complements the long-term symptomatic relief observed with ruxolitinib. Patients treated with ruxolitinib experienced sustained improvement in total symptom scores (TSS) over 52 months, reflecting its efficacy in alleviating the chronic symptoms of PV.2 56% of patients achieved a >50% reduction in JAK2V617F allele burden at the final timepoint, compared to 25% in the BAT group.2 Infection rates were generally comparable across categories, with most being low-grade.11 These included respiratory (33% vs. 28%), cutaneous (22% vs. 16%), genitourinary (12% vs. 10%), gastrointestinal (10% vs. 9%), and herpes zoster virus infections (9% vs. 3%).11

|

Real-world impact: A patient’s journey to ruxolitinib Prof. McMullin then introduced the case of a 60-year-old female with JAK2V617F-positive PV who presented with a transient ischemic attack (TIA), headaches, and severe pruritus. Classified as high-risk, she was initially managed with occasional venesection and HU. Despite HU therapy, she remained symptomatic, experiencing persistent fatigue and worsening pruritus. In early 2021, she required four venesections within three months, and her blood counts remained elevated with a hemoglobin level of 156g/L, hematocrit of 0.42, white cell count of 12.8×109/L, and platelet count of 714×109/L, indicating inadequate disease control. In April 2021, she was initiated on ruxolitinib at a dose of 10mg twice daily. Within just four weeks, her symptoms significantly improved. The pruritus subsided, venesections were no longer required, and her blood counts normalized. This case exemplifies the rapid and meaningful clinical benefit of ruxolitinib in a patient with HU intolerance and persistent disease burden. It also raises an important clinical question—should the transition to ruxolitinib have occurred earlier? |

Clinical implications: Rethinking PV treatment pathways

The findings from the MAJIC-PV trial, along with real-world clinical experiences, demonstrate that ruxolitinib provides a durable and comprehensive response in PV patients who are resistant or intolerant to HU.2 Its clinical benefits make it a valuable option after HU resistance or intolerance.2 Prof. McMullin highlighted that early recognition of HU failure is essential. Delaying the transition to ruxolitinib can result in prolonged symptom burden, increased risk of complications, and diminished quality of life. Clinicians must remain vigilant in monitoring treatment response and consider ruxolitinib promptly when signs of HU intolerance or resistance emerge. This highlights the importance of integrating ruxolitinib into routine clinical practice to optimize patient care.1

Conclusion

Ruxolitinib has been shown to address critical unmet needs in the management of high-risk PV.2 For patients resistant or intolerant to HU, it offers superior disease control, symptom relief, and improved EFS.2 Prof. McMullin concluded that as PV management continues to evolve, the integration of targeted therapies like ruxolitinib into clinical practice will be essential, and in doing so, clinicians can ensure that patients receive the most effective treatment available, ultimately improving their quality of life and long-term prognosis.