EXPERT INSIGHT

Beyond breathlessness: The evolving landscape of ILD management

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) presents as a diverse group of lung disorders, where inflammation and fibrosis drive a highly variable disease course.1,2 While some patients experience mild symptoms, others progress to debilitating respiratory failure, highlighting the unpredictable nature of ILD.1,2 In an interview with Omnihealth Practice, Dr. Syazatul Syakirin Sirol Aflah, a respiratory physician specializing in ILD at Institut Perubatan Respiratori, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia shed light on the complexities of ILD and its management. A prominent contributor to ILD research, particularly in idiopathic (IPF) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis (PPF), and biomarker applications, Dr. Sirol Aflah shared her insights on the global and Malaysian burden of ILD, advancements in diagnostics and treatment, and the future direction of ILD management, offering valuable perspectives for healthcare professionals.

Uncovering the rising burden of ILD: Global trends and regional challenges

ILD encompasses a heterogeneous group of >200 lung disorders, all characterized by inflammation and progressive fibrosis of the lung interstitium.1 The global burden of ILD is rising, driven by aging populations, environmental exposures, and increasing diagnostic awareness.1-3 Among its subtypes, IPF is the most extensively studied, with an estimated prevalence ranging from 3.3-45.1 cases per 100,000 individuals worldwide, depending on population demographics and diagnostic criteria.2,4

While IPF remains the most widely researched ILD subtype, in Malaysia, autoimmune-related ILDs and hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) constitute a significant proportion of PPF cases.2,5,6 Real-world data from Asia’s largest ILD epidemiology study, using the ICD-9-CM coding system and featuring the longest follow-up, suggests that post-inflammatory pulmonary fibrosis (PiPF) was the most frequent subtype of incident ILD (79.8%), followed by idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP) (12.5%), sarcoidosis (4.0%), connective tissue disease (CTD)-ILD (2.0%), and hypersensitivity pneumonitis (1.7%).7 Reflecting on her own center’s experience, Dr. Sirol Aflah observed a steady rise in ILD diagnoses, with new cases exceeding 100 patients per year.

Ethnic differences in ILD prevalence also warrant attention.7 Globally, ILD is more commonly observed in people of color, particularly individuals of Black/African and Asian ancestry.8 A similar pattern is reflected in Malaysia, where PPF phenotype was found to be prevalent among individuals of Indian descent compared to Malay or Chinese populations.5 This suggests a potential genetic or environmental influence on disease susceptibility across different ethnic groups.7

The science of ILD: Understanding the pathophysiology to predict disease progression

The course of ILD varies widely depending on the underlying subtype.2 IPF is the most aggressive form, marked by relentless fibrosis and a median survival of just 2-3 years after diagnosis.7 In contrast, CTD-ILD often has an inflammatory component that may respond to immunosuppressive therapy, leading to a more variable disease trajectory.5,6

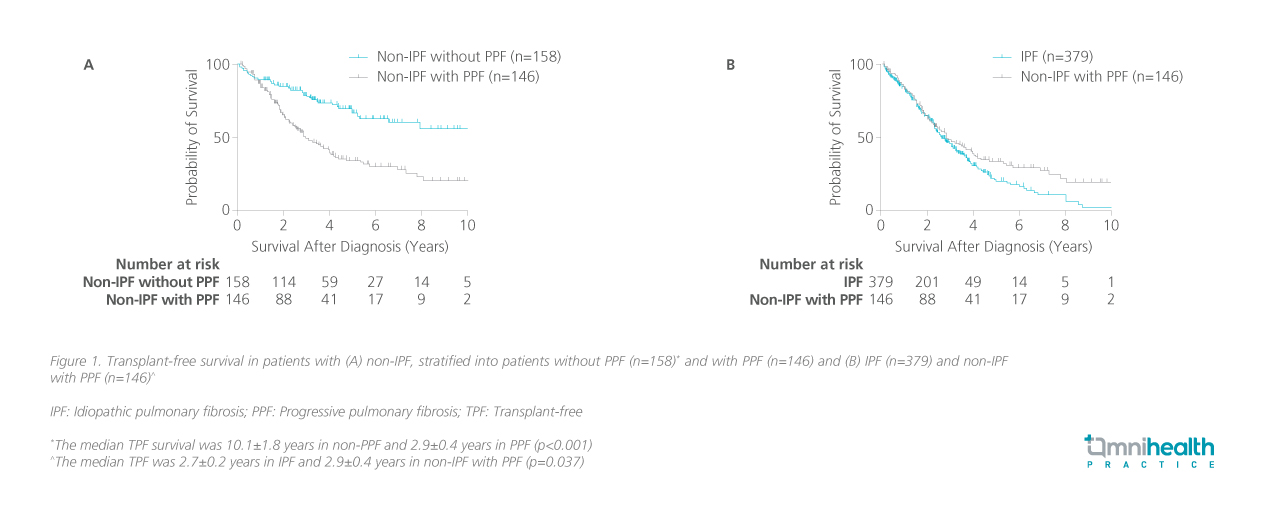

Some patients with non-IPF ILD develop PPF phenotype, which is associated with a poor prognosis.1 These patients have a median transplant-free survival (TPF) of just 2.9±0.4 years, and in the first three years after diagnosis, their survival closely resembles that of IPF patients (figure 1).1

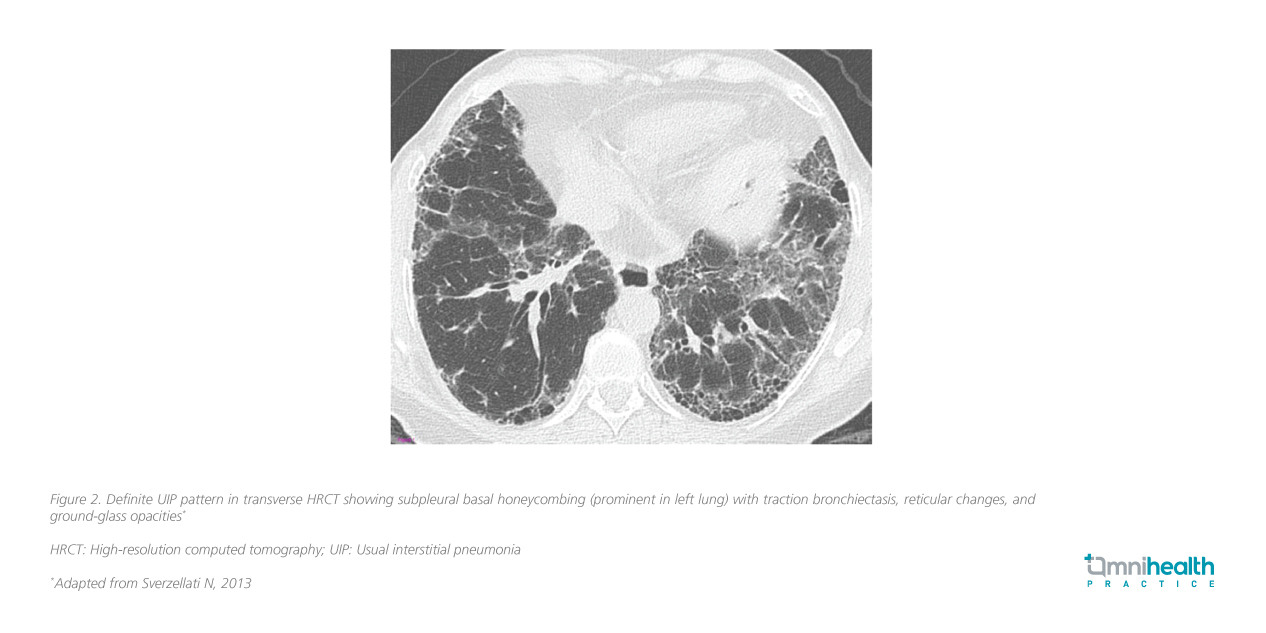

Fibrosis and inflammation are central to ILD pathogenesis, with progressive lung scarring impairing gas exchange, leading to respiratory failure in advanced cases.1,2 Usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) is a key high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) pattern characteristic of IPF and some advanced fibrotic ILDs (e.g., CTD-ILD, chronic HP, asbestosis) (figure 2).3,6 In the right clinical context, HRCT alone may suffice for an IPF diagnosis without biopsy.3

Forced vital capacity (FVC) and diffusing capacity of lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) are widely recognized as strong prognostic indicators in ILD.9 According to Dr. Sirol Aflah, “The integration of FVC decline and DLCO with patient- and disease-specific variables improve our ability to predict patient outcomes and guide treatment decisions.”

To better classify ILD progression, the American Thoracic Society (ATS) introduced PPF as a unifying definition for fibrosing ILDs that demonstrate progressive deterioration despite conventional treatment in 2022.1 PPF is defined by at least two of the following criteria within one year:1,6

- Worsening respiratory symptoms (cough and/or dyspnea)

- Declining lung function (≥5% absolute decline in FVC and/or ≥10% absolute decline in DLCO)

- Radiological progression of fibrosis

HRCT plays a critical role in identifying ILD progression.3,6 While fibrosis may be subtle in early stages, advanced disease is marked by extensive honeycombing and reticulation patterns.6 She emphasized that prognosis is highly dependent on disease status at presentation, with earlier diagnosis and treatment correlating with better long-term outcomes.10 Beyond traditional lung function measures, serum biomarkers such as Krebs von den Lungen-6 (KL-6) and surfactant protein D (SP-D) have gained recognition for their role in predicting disease progression and treatment response.11 Their growing clinical utility highlights the need for further research and standardized integration into ILD management.6

Overcoming diagnostic hurdles and optimizing monitoring

Diagnosing ILD remains challenging due to its non-specific symptoms, overlapping clinical features, and heterogeneous subtypes.12 Dr. Sirol Aflah highlighted that in the past, ILD was broadly classified as a diffuse parenchymal disease without proper subtyping, leading to suboptimal management. This underscores the importance of expertise in both clinical and radiological ILD assessment, with a radiologist trained in thoracic imaging playing a key role in enhancing diagnostic confidence and accuracy.3,13

HRCT remains the gold standard for ILD diagnosis, offering detailed visualization of interstitial abnormalities.3 While UIP is characteristic of IPF, it can also be seen in CTD-ILD and chronic HP, creating diagnostic uncertainty.3 Multidisciplinary discussions, particularly between pulmonologists and radiologists, are essential for accurate classification and treatment selection, while a diagnostic algorithm can further support diagnosis.3,6 Figure 3 delineates the 2022 ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline consensus on IPF diagnosis based on HRCT and biopsy patterns.6

In IPF, annual HRCT scans are recommended due to the increased risk of malignancy.6 In contrast, other ILD subtypes, such as HP and CTD-ILD, are typically monitored through clinical assessment and pulmonary function tests rather than routine imaging.6,14 Additional assessments may include body plethysmography to measure total lung capacity (TLC), though TLC is not a strong prognostic marker; DLCO to evaluate gas exchange efficiency; and the six-minute walk test (6MWT) to assess exercise capacity and functional impairment.6 Therefore, monitoring strategies may vary based on the specific ILD subtype and its management approach.

Beyond one-size-fits-all: Tailoring ILD treatment to patient needs

Historically, ILD was often considered a terminal disease, with treatment focusing solely on symptom management until patients became oxygen-dependent.15 However, the advent of antifibrotic therapies has gradually transformed this outlook.6,14

The treatment landscape for ILD is largely dependent on the underlying disease pathology.6 While inflammatory-driven ILD subtypes, such as CTD-ILD and HP, often benefit from immunosuppressive therapy, progressive fibrotic forms, including IPF and PPF, require antifibrotic agents.6 Dr. Sirol Aflah emphasized the transformative impact of antifibrotic therapy in ILD management, stating: “Antifibrotic therapy has significantly changed the treatment paradigm for IPF. However, accessibility remains a major challenge.“

Expanding indications for antifibrotic therapy could offer new treatment avenues for a broader ILD population. Among antifibrotic agents, nintedanib and pirfenidone are the mainstays of treatment for IPF.13,14 While both have demonstrated efficacy in slowing disease progression, Dr. Sirol Aflah explained that treatment selection is often guided by factors such as pill burden, side effect profiles, and patient lifestyle. As ILD management evolves, a multidisciplinary, patient-centered approach remains key to optimizing outcomes.13

Beyond the horizon: Advances in research and collaborative care

Ongoing research efforts is reshaping the ILD landscape, driving the refinement of prognostic tools and the expansion of therapeutic options.9,14,16 Dr. Sirol Aflah highlighted this shift as a positive step forward, reflecting a growing commitment to addressing unmet patient needs. Notably, two investigational therapies targeting fibrosis reversal are emerging as promising advancements, with phase 2 trials underway to evaluate their potential efficacy and safety.17,18

As the therapeutic landscape continues to expand, multidisciplinary collaboration remains pivotal in optimizing patient care.13 Dr. Sirol Aflah also shared some key takeaways:

- Increasing ILD awareness among both HCPs and the public is crucial in reducing diagnostic delays and optimizing patient care

- Early diagnosis is key to detecting ILD before disease progression

- Differentiating between ILD subtypes is essential for guiding treatment options

- Multidisciplinary collaboration significantly improves diagnostic accuracy and treatment outcomes

Conclusion

“Stabilization in ILD is difficult to quantify. However, the absence of exacerbations, no hospitalizations, and maintaining a good quality of life are key markers of positive outcomes,” she highlighted. As ILD research progresses, so do opportunities for earlier diagnosis, improved prognostic tools, and expanded treatment options.7,10 The evolving role of antifibrotics, the promise of emerging therapies, and the strength of multidisciplinary collaboration continue to reshape the ILD treatment paradigm, ultimately improving patient outcomes and quality of life.5,10,16,17

“Stabilization in ILD is difficult to quantify. However, the absence of exacerbations, no hospitalizations, and maintaining a good quality of life are key markers of positive outcomes”

Dr. Syazatul Syakirin Sirol Aflah

Consultant Respiratory Physician,

Institut Perubatan Respiratori (IPR),

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia