Heart failure (HF) is often underrecognized despite early warning signs.1 Delays in diagnosis and appropriate treatment can significantly worsen prognosis.1 By the time a patient is hospitalized for HF (HHF), the risk of rehospitalization and mortality has greatly increased.2,3 In a recent webinar, Professor Javed Butler from the University of Mississippi, United States, discussed data on the use of empagliflozin in HF patients, highlighting the benefits of early initiation in both chronic and acute settings as reflected by the latest guidelines. He also emphasized that medications such as sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2is) exert a comprehensive impact across diverse cardio-kidney-metabolic (CKM) conditions due to their direct and indirect actions, which collectively offer risk reduction across these interconnected disease states.

A call for early intervention with SGLT2is in HF and other CKM conditions

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) such as HF exist as a continuum, and patients are at risk of cardiovascular (CV) events irrespective of diagnosis.4 Prof. Butler lamented that “the number one place of HF diagnosis is the emergency room (ER), not because it was discovered in the ER, but because the symptoms have been ignored for months.” Delays in HF diagnosis at hospitalization can lead to substantially worse outcomes including a 30% readmission rate within 60-90 days and a 30% mortality rate within 1 year.2,3 Prof. Butler stated that timely treatment is essential to prevent additional damage and that simple assessments such as H2FPEF scores offer a rapid way to stratify and diagnose patients.

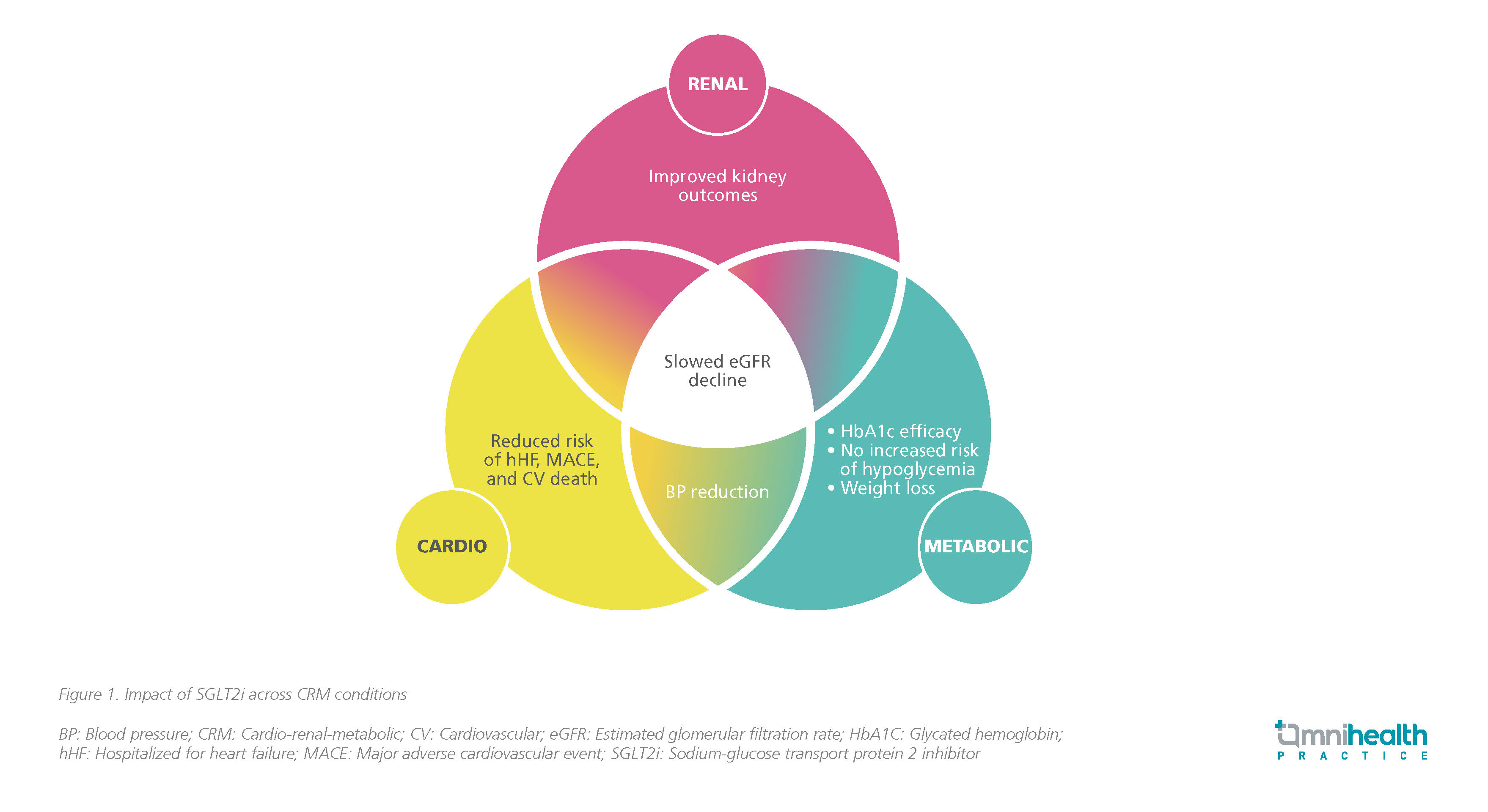

Given the interconnectedness of CKM conditions, medications such as SGLT2is offer benefits across many of these diseases as illustrated by a diagram shared by Prof. Butler (figure 1). Among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), early use of SGLT2i has been shown to provide cardio-reno protective benefits and reduce CV mortality.5,6 The common pathophysiology in the development and progression of HF revealed that medications previously used upstream to address the risk factors of HF can also be used downstream to prevent CV events.4

The established and consistent benefit of empagliflozin in CHF

The CV benefits of SGLT2is such as empagliflozin are well-supported in clinical studies.5 In the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial, empagliflozin was the only oral antidiabetic (OAD) to show reductions in CV mortality in T2DM patients with established CV disease.5 This has prompted investigations of its effect on patients with chronic HF (CHF).7,8 Two key studies, namely the EMPEROR-Reduced and EMPEROR-Preserved studies, examined the effects of empagliflozin in patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), respectively.7,8

The EMPEROR-Reduced is a phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in which HFrEF patients who received empagliflozin were associated with a 25% reduction in the time to CV death or HHF (hazard ratio [HR]=0.75; 95% CI: 0.65-0.86; p<0.001) compared to those who had received placebo.7 Similar results were observed in the population with HFpEF in the sister trial EMPEROR-Preserved.7,8 In the HFpEF population, the benefit of a 21% reduction in the risk of CV death or HHF was maintained (HR=0.79; 95% CI: 0.69-0.90; p<0.001).8

Additionally, in both trials, empagliflozin not only offered clinical improvements but also in terms of Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) quality of life (QoL) outcomes.9,10 Early and sustained benefits with a consistently higher likelihood of improvement and a lower likelihood of deterioration were seen among responders of empagliflozin across different domains.9,10

EMPULSE: Frontloading benefits through early therapy in AHF

Beyond the chronic setting, the benefits of SGLT2is apply to patients with acute HF (AHF) as demonstrated by the randomized phase 3 EMPULSE trial, where empagliflozin was initiated in an in-hospital setting in patients with AHF who were clinically stable.11 In-hospital initiation with early SGLT2i use along with other medications has been associated with better outcomes such as increased likelihood of the patient being treated, tolerating the treatment, filling prescriptions, adhering to the regimen, persisting with therapy, feeling better, being discharged, and survival.12 Prof. Butler said that traditionally, AHF trials were conducted to evaluate the safety of the therapy in this population, but in the case of empagliflozin, there is a potential for efficacy that needs to be tested as well.

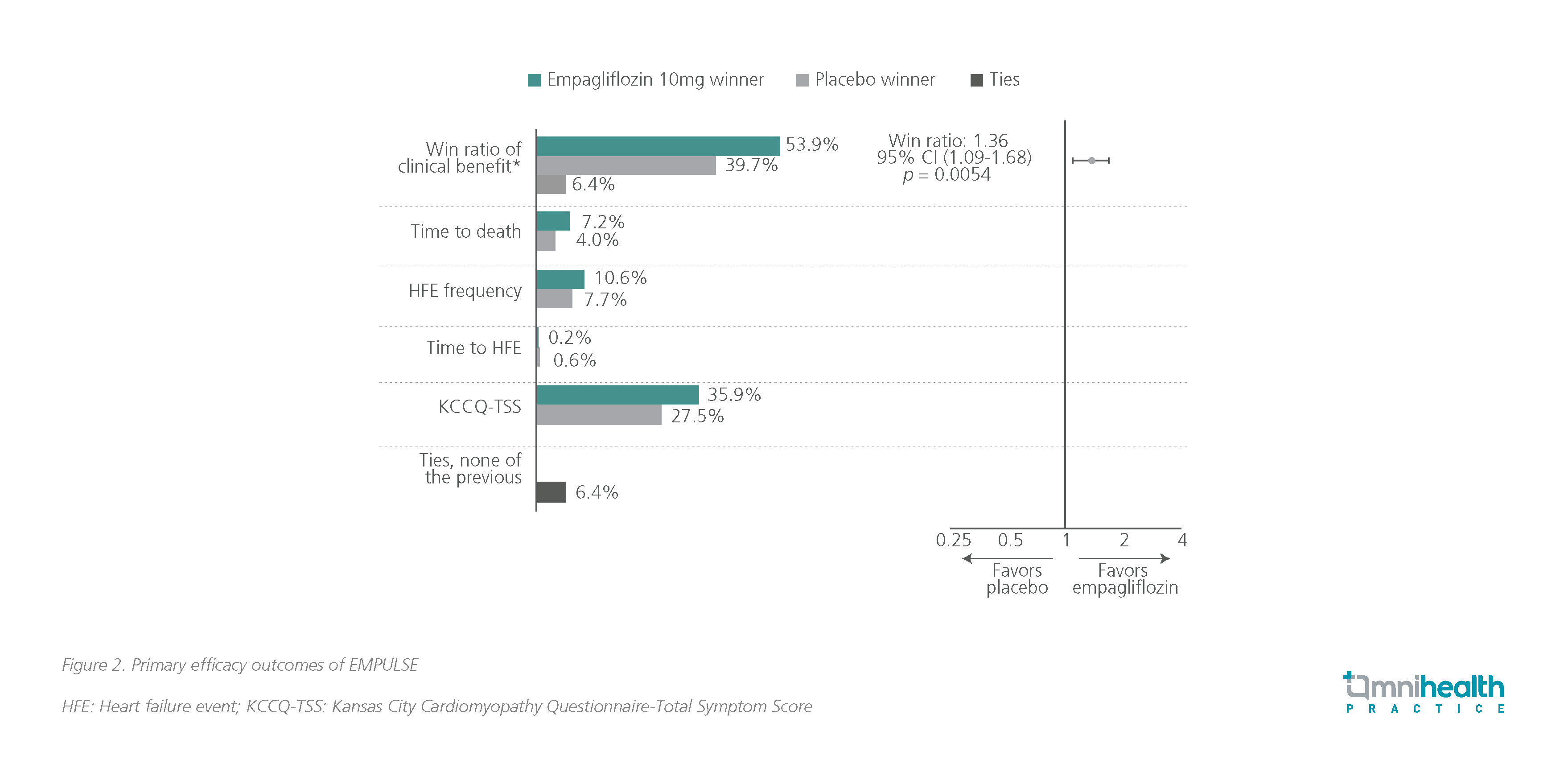

In EMPULSE, participants (n=530) with a primary diagnosis of acute de novo or decompensated CHF regardless of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) were randomized to receive empagliflozin 10mg QD or placebo during hospitalization when clinically stable (median time from hospital admission to randomization: 3 days) and treated for up to 90 days.11 It revealed that patients with AHF who took empagliflozin had reduced rates of death or rehospitalization, and reported better QoL than those in the placebo group.11 The stratified win ratio was 1.36 (95% CI: 1.09-1.68; p=0.0054), implying that patients treated with empagliflozin were 36% more likely to experience clinical benefit compared with placebo (figure 2).11 Safety outcomes were comparable between the two arms showing that even in an acute setting, empagliflozin was well tolerated.11 Additionally, empagliflozin achieved a higher mean adjusted weight loss of 1.5kg (95% CI: -2.8 to -0.3; p=0.0137), which infers effective decongestion for these patients.14

The statistically significant and early improvement in prognosis in terms of reduction in rehospitalization and mortality highlighted the benefits of prompt empagliflozin initiation before discharge to maximize the protective effects of empagliflozin during the most vulnerable 90-day period following discharge.11,14

Fundamental updates for timely SGLT2i initiation in GDMT

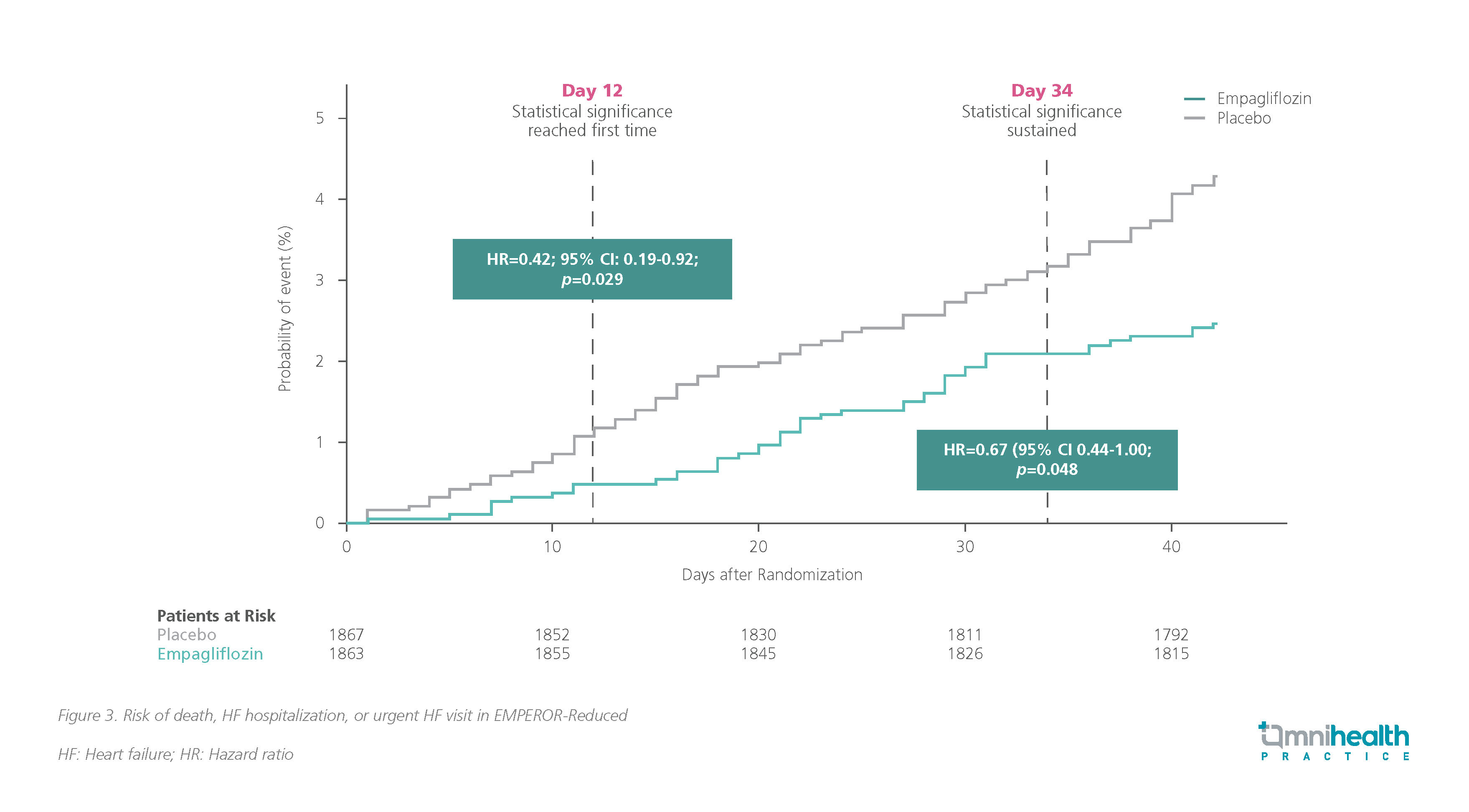

Robust data across both CHF and AHF have showcased the benefits of early empagliflozin use.7,8,11 In both HFrEF and HFpEF populations, the benefits of empagliflozin were shown to be statistically significant very early in the treatment.15,16 A retrospective analysis of the EMPEROR-Reduced trial found that patients treated with empagliflozin experienced substantial benefits in time to death, first occurrence of HHF or urgent care visit for worsening HF.15 This treatment effect was observed as early as day 12 compared to the placebo group (HR=0.42; 95% CI: 0.19-0.92; p=0.029) (figure 3).15 Similarly, a significant benefit in the same metric was shown as early as 18 days after empagliflozin initiation in the EMPEROR-Preserved population.16 The rapid onset of benefits observed provides insights into the timing and sequence of SGLT2i treatment in HF.

Previously, guidelines had suggested a sequential initiation of the four pillars of HF treatment including angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs), beta-blockers (BBs), mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs), and SGLT2is.17 However, under this framework, patients are exposed to unnecessary risk during a prolonged process of initiation and titration, worsened by clinical inertia.17 In Prof. Butler’s remarks, he emphasized that “sequencing is a historical construct, and not a biological one” and noted that the growing recognition of how SGLT2is can address underlying disease processes both directly and indirectly has prompted updates to clinical practice guidelines. Prof. Butler stressed that the risk associated with omitting GDMT greatly outweighs any risks of administering it as omission can lead to lower survival and QoL.

In patients with HFpEF, the 2023 American College of Cardiology (ACC) Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Management of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction further specified that SGLT2is should be initiated in all patients without contraindications.18 In the management of HFrEF, the 2022 American Heart Association (AHA)/ACC/Heart Failure Society of America (HFSA) HF guidelines recommend the initiation of all 4 pillars of medications with no specific sequencing after diagnosis.19 Furthermore, the 2023 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines also recommend the initiation of oral medication before discharge in the AHF population and highlighted the first-line positioning of SGLT2is such as empagliflozin for HF patients across the LVEF spectrum.20

Prof. Butler summarized a few pointers that have been reflected in updates across both European and American guidelines.18-20 The first is that speed matters and we have been too slow in introducing life-saving therapies in the past. Secondly, initiation should be prioritized over up-titration, and multiple pillars should be initiated as soon as possible without a fixed order or sequencing. Additionally, these medications may enable a higher tolerance of each other. For instance, SGLT2is decreases the risk of hyperkalemia and slows the progression of renal dysfunction, in turn facilitating the use of ARNIs and MRAs, and may even help with diuretic resistance.

Conclusion

SGLT2is such as empagliflozin offer multiple benefits across various cardio-renal-metabolic conditions by addressing the underlying pathophysiology and mitigating the damage caused by upstream risk factors.4-6 In patients with HF, early initiation of empagliflozin offers many benefits across the LVEF spectrum in both acute and chronic settings.7-11,13 Particularly among AHF patients, the initial days following hospitalization represent a window of heightened vulnerability where earlier initiation of empagliflozin may prove pivotal in securing improved clinical outcomes.2,3,11 The benefits of early treatment in both chronic and acute settings are now recognized and reflected in the latest clinical practice guidelines.11,15,16,18-20

This is an independent editorial article, published and distributed through unrestricted educational support from the pharmaceutical community, for the purpose of continuing medical education only. The views expressed in this publication reflect the experience and/or opinion of the author(s) and are not necessarily those of editors, publisher, and sponsor(s). Because of rapid advances in medicine, independent verification of clinical diagnoses, medical suitability and dosage should be made before treatment prescription. The appearance of advertisement, if any, has no influence on editorial content or presentation and does not imply the endorsement of products by the publication, or its authors and editors.

- Wong CW, et al. Misdiagnosis of Heart Failure: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J Card Fail. 2021;27(9):925-933.

- Khan MS, et al. Trends in 30- and 90-Day Readmission Rates for Heart Failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2021;14(4):e008335.

- Hung WK, et al. One-Year Mortality Risk Stratification in Patients Hospitalized for Acute Decompensated Heart Failure: Construction of TSOC-HFrEF Risk Scoring Model. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2020;36(3):240-250.

- Dzau VJ, et al. The cardiovascular disease continuum validated: clinical evidence of improved patient outcomes: part I: Pathophysiology and clinical trial evidence (risk factors through stable coronary artery disease). Circulation. 2006;114(25):2850-70.

- Zinman B, et al. Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2117-28.

- Wanner C, et al. Empagliflozin and Progression of Kidney Disease in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):323-34.

- Packer M, et al. Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes with Empagliflozin in Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(15):1413-1424.

- Anker SD, et al. Empagliflozin in Heart Failure with a Preserved Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(16):1451-1461.

- Butler J, et al. Empagliflozin and health-related quality of life outcomes in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the EMPEROR-Reduced trial. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(13):1203-1212.

- Butler J, et al. Empagliflozin, Health Status, and Quality of Life in Patients With Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction: The EMPEROR-Preserved Trial. Circulation. 2022;145(3):184-193.

- Voors AA, et al. The SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin in patients hospitalized for acute heart failure: a multinational randomized trial. Nat Med. 2022;28(3):568-574.

- Greene SJ, et al. In-hospital initiation of quadruple medical therapy for heart failure: making the post-discharge vulnerable phase far less vulnerable. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022;24(1):227-229.

- Kosiborod MN, et al. Effects of Empagliflozin on Symptoms, Physical Limitations, and Quality of Life in Patients Hospitalized for Acute Heart Failure: Results From the EMPULSE Trial. Circulation. 2022;146(4):279-288.

- Voors AA, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Empagliflozin in Hospitalized Heart Failure Patients: Main Results From the EMPULSE Trial. Presented at American Heart Association Scientific Sessions 2021; Nov 13-15, 2021; online.

- Packer M, et al. Effect of Empagliflozin on the Clinical Stability of Patients With Heart Failure and a Reduced Ejection Fraction: The EMPEROR-Reduced Trial. Circulation. 2021;143(4):326-336.

- Packer M, et al. Effect of Empagliflozin on Worsening Heart Failure Events in Patients With Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction: EMPEROR-Preserved Trial. Circulation. 2021;144(16):1284-1294.

- Khan MS, et al. Simultaneous or rapid sequence initiation of medical therapies for heart failure: seeking to avoid the case of 'too little, too late'. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23(9):1514-1517.

- Kittleson MM, et al. 2023 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Management of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;81(18):1835-1878.

- Writing Committee Members; ACC/AHA Joint Committee Members. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure. J Card Fail. 2022;28(5):e1-e167.

- McDonagh TA, et al. 2023 Focused Update of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2023;44(37):3627-3639.