INDUSTRY ESSENTIALS

Forging the framework for anal cancer detection among high-risk populations: The IANS consensus guidelines for anal cancer screening

Anal cancers are predominantly preceded by screening-detectable high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSILs).1 Despite being relatively uncommon in the general population, possessing an incidence rate of 1.7 per 100,000 person-years, anal cancers disproportionately affects specific groups of individuals, particularly people with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), solid organ transplant recipients and women with a history of vulvar cancer or precancer.1

Given the recent establishment that treating anal HSIL reduces the risk of anal cancer in people with HIV, and the emergence of data on the risk of anal cancer among other groups and the performance of anal cancer screening tests, pre-existing anal cancer screening guidelines would benefit from an update.1-2 As such, the International Anal Neoplasia Society (IANS) developed consensus guidelines for anal cancer prevention and early detection to assess the needs, develop evidence-based guidance, and address knowledge gaps in anal cancer screening.1

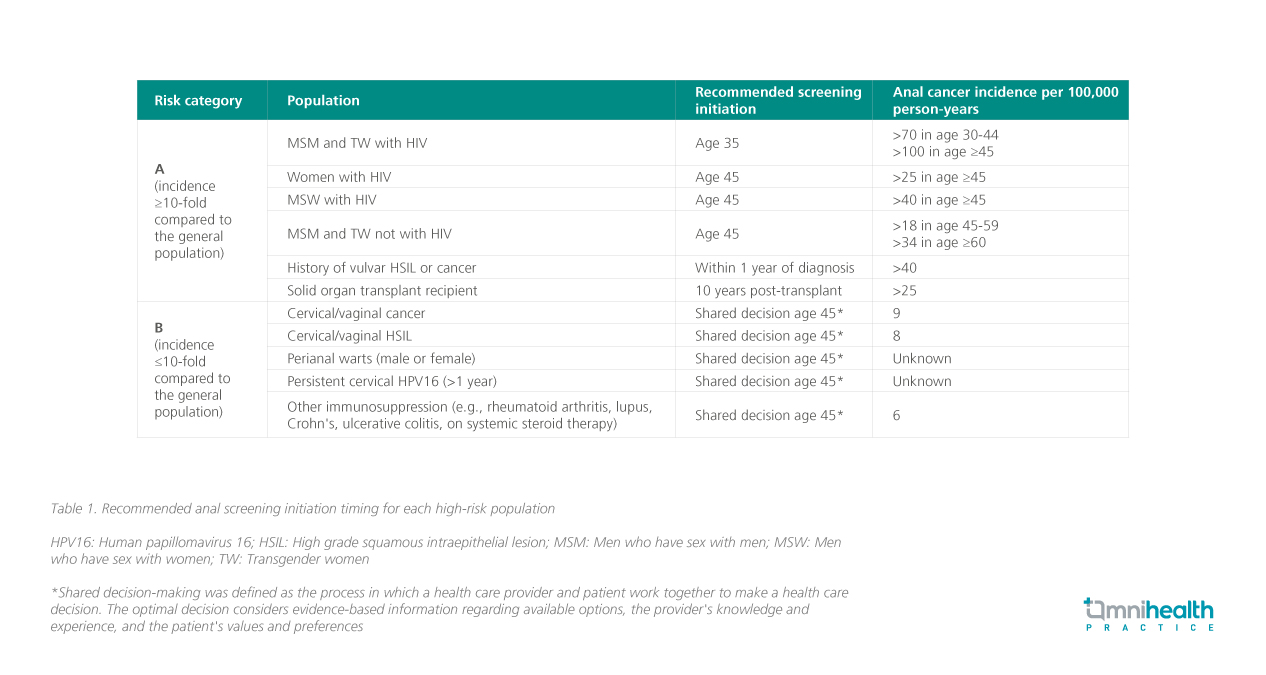

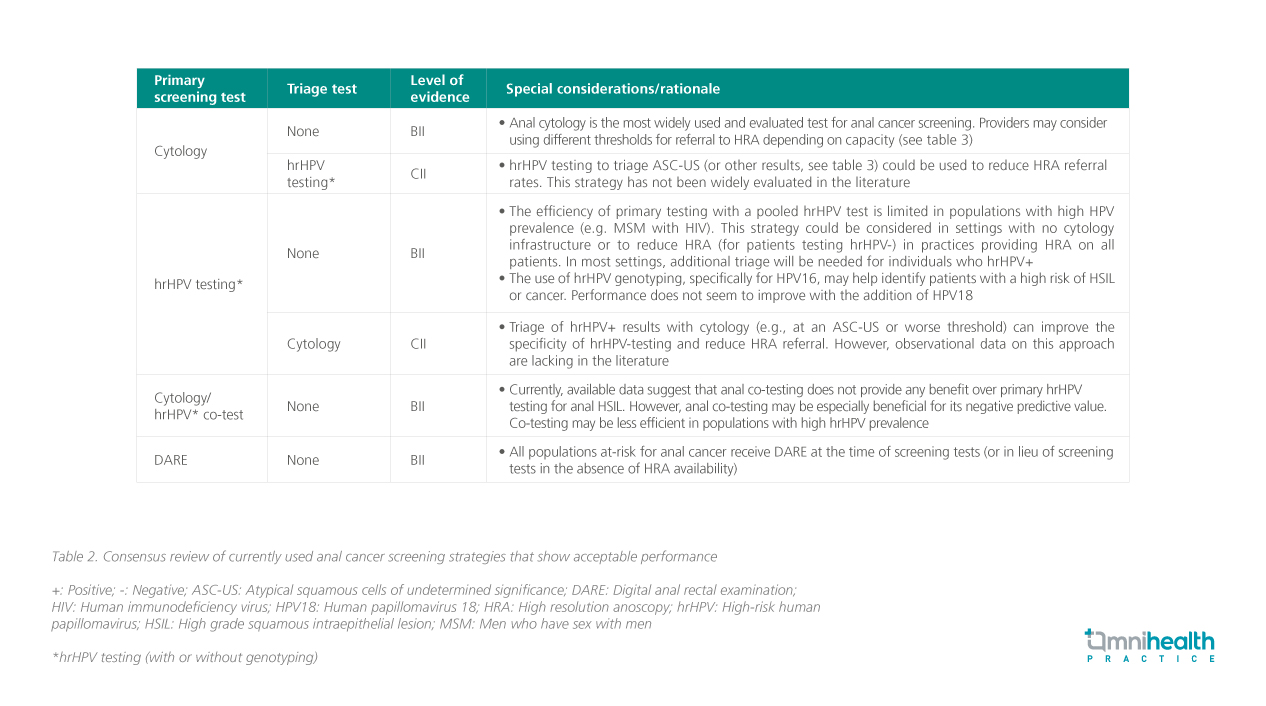

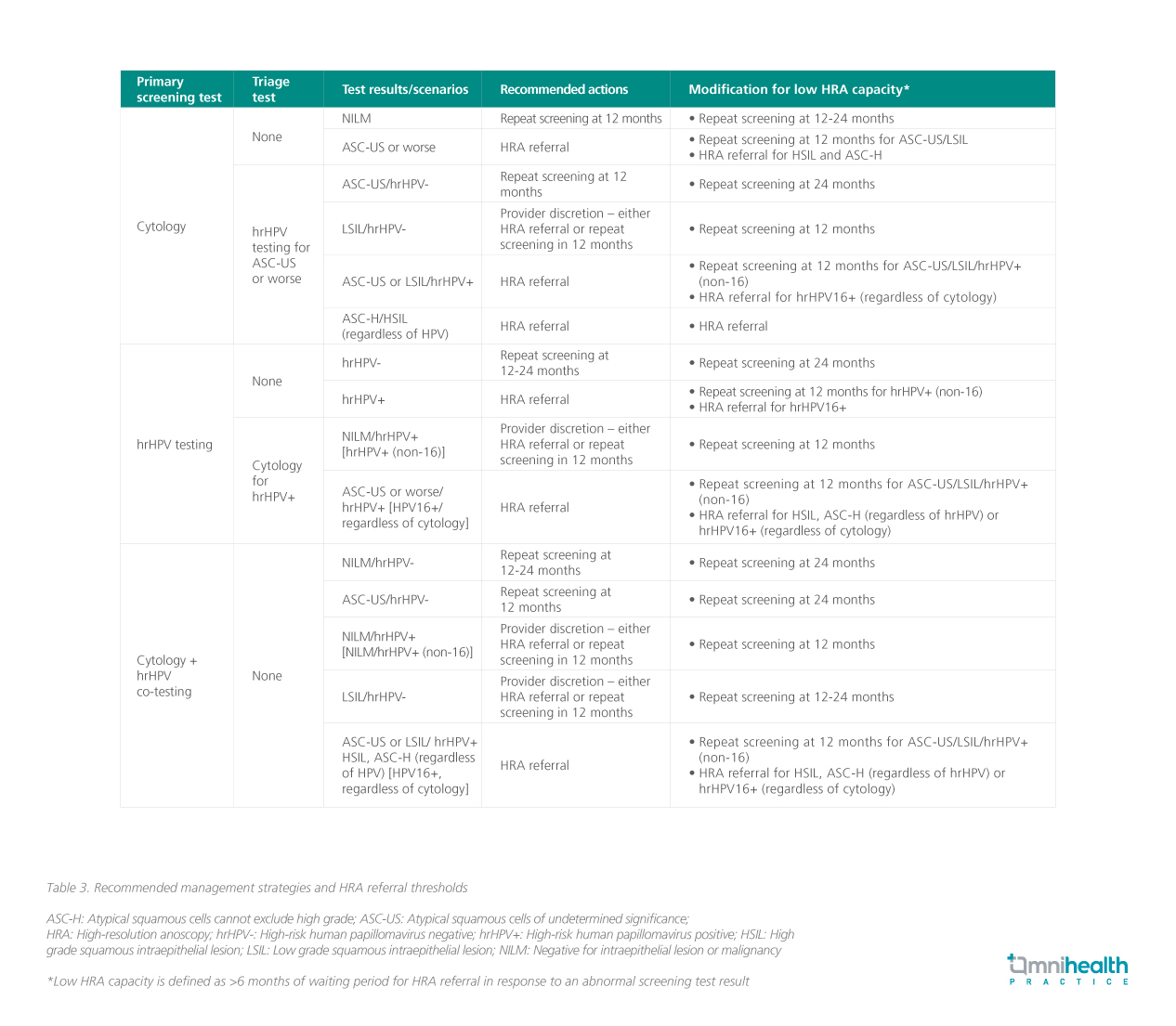

The initial IANS task force comprised 17 international experts representing 6 countries with a wide range of professional expertise including epidemiology, decision science, pathology, public policy, infectious diseases, gynecology, colorectal surgery and high-resolution anoscopy (HRA) providers. To account for variability in discipline, geography, and under-represented populations, the IANS task force was expanded to a total of 60 experts, which represents 19 countries.1 Priority areas for guideline improvement included establishing (1) the populations to screen based on the evaluation of anal cancer incidence in each group (table 1), (2) the screening tools to recommend (table 2), and (3) the management of results and threshold for HRA referral (table 3).1 Recommendation strength (A-E) and quality of evidence (I-III) using the same grading system applied to the US multi-organizational cervical cancer screening and management guidelines were assigned where applicable.1

|

In an interview with Omnihealth Practice, Dr. Wong, Tin-Yau Andrew, an infectious disease specialist, shared his insights on the current local practices in managing patients with anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSILs) or anal cancer, and potential challenges in anal cancer prevention. |

Current anal cancer management strategies in Hong Kong

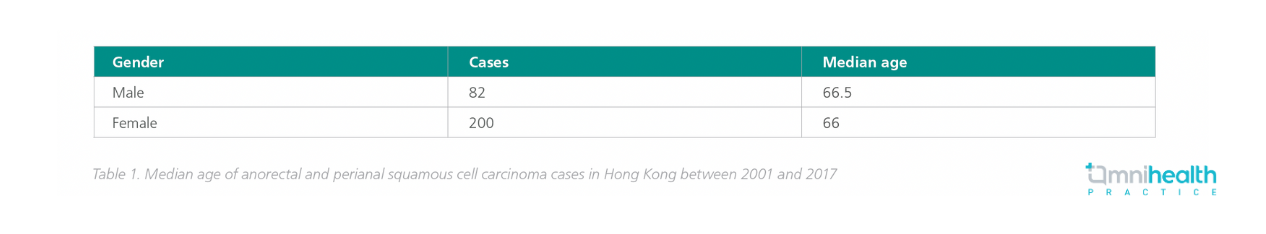

Anal cancer is relatively uncommon in the general population of Hong Kong. However, specific populations face a higher risk of developing anal cancer such as people living with human immunodeficiency virus HIV (PLHIV), men who have sex with men (MSM), transgender women, and individuals with a weakened immune system (e.g. solid organ transplant recipients and patients with autoimmune disorders who are treated with immunosuppressants). According to statistics from the Hong Kong Cancer Registry, the incidence rate of anal cancer has also been consistently higher in women compared to men (figure 1 and table 1), which may be attributed to cervical and vulvar cancer being closely associated with anal cancer.

Chemoradiation (CR) therapy and surgery are the cornerstones of treating anal cancer. In the case of anal HSILs, while topical treatment such as imiquimod cream may be used to enhance mucosal immunity against infections, additional methods such as electrocautery or laser therapy may be necessary for lesion removal. It is crucial to emphasize that the success of these treatment modalities greatly relies on prompt initiation, underscoring the significance of early detection and intervention in managing anal cancer effectively.

Potential hurdles in local anal cancer screening implementation

Regardless of the choice of screening modality (cytology, HPV-typing tests or cytology-HPV co-test), high-resolution anoscopy (HRA) should be performed in individuals with abnormal screening results to verify the diagnosis of anal HSILs and cancer. However, the accessibility of HRA has been a bottleneck in the screening and diagnosis of anal cancer. In Hong Kong, resources and expertise to perform HRA are limited, with HRA facilities only available in a few institutions, resulting in long HRA referral times.

Given the inadequate HRA resources and long HRA referral time in Hong Kong, digital anal rectal examination (DARE) should be performed, such as at regular check-ups and when symptoms appear in at-risk populations, to detect early anal lesions via palpation. Integrating anal cancer screening protocols as an extension to the cervical screening program in Hong Kong may also be feasible, given the close association between cervical and anal cancers, and the similarities in risk factors and screening algorithms.

The significance of physician training and patient education

In addition to technical limitations, the inadequate awareness among the local healthcare community also poses a significant challenge to the effectiveness of anal cancer screening which often leads to delayed diagnosis. For instance, some physicians may misinterpret the early signs of anal cancers, such as rectal bleeding, as hemorrhoids. Moreover, there are common misconceptions prevalent among the general public regarding anal cancer. These include the belief that anal cancer is primarily associated with anal sex, overlooking hygiene-related risk factors (such as post-toilet wiping behavior), and assuming that colorectal cancer screening results are sufficient for detecting anal cancer. Addressing these misconceptions and increasing awareness among the public is crucial for improving the detection of anal cancer.

To facilitate these improvements, it is essential to prioritize patient education and physician training. By providing accurate information and raising awareness about the symptoms, risk factors, and screening methods for anal cancer, individuals can be better equipped to seek timely medical attention. Additionally, fostering collaborations between infectious disease specialists, gynecologists, organ transplant physicians and colorectal surgeons can enhance their collective awareness and vigilance towards anal cancer, leading to more proactive and effective detection and management strategies.