MEETING HIGHLIGHT

Drugging the undruggable KRAS with sotorasib, the first-in-class KRASG12C inhibitor for advanced NSCLC

Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homologue (KRAS) is the most common driver oncogene in human cancers with a poor prognosis, yet considered untargetable by small molecule drugs.1-3 However, this perception has now been challenged with the recent United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s accelerated approval of sotorasib, the first-in-class small drug molecule that can specifically inhibit the KRASG12C protein, for treating adult patients with KRASG12C‑mutated locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC.4,5 In the recent Immuno-Oncology Hong Kong 2021 organized by the Department of Clinical Oncology and the Hong Kong Cancer Institute in conjunction with the State Key Laboratory of Translational Oncology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Dr. Bob T. Li, Medical Oncologist from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, raised the unaddressed issues of targeting KRAS and its specific mutant version, KRASG12C, and highlighted the results of CodeBreaK 100, the trial that investigated sotorasib, as well as the importance of testing for KRAS routinely.

KRASG12C as one of the most common mutations in NSCLC with poor prognosis

Representing approximately 25% of the identifiable oncogenic drivers, KRAS is the most common driver oncogenes in human cancers.2 Despite its high prevalence, KRAS has long been regarded as undruggable owing to the lack of binding pockets of the KRAS protein as well as the narrow therapeutic index of downstream inhibitors, thus impeding the approval of targeted therapies.3,6,7

Worse still, KRAS mutation is associated with poor prognosis and is predictive of poor treatment outcomes.1,8 When compared to wild-type, aggregated results from studies using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) revealed that NSCLC patients with KRAS mutation have worse survival (HR=1.40; 95% CI: 1.18-1.65).9 Specifically, KRASG12C, a result of a glycine-to-cysteine amino acid substitution at codon 12, is one of the most frequent mutated versions of KRAS that accounts for approximately 25% of all KRAS mutations in Asian NSCLC patients.10,11 Although Asian patients with NSCLC have less KRASG12C mutations than the black and the white patient populations, the Asian male patients still harbor KRASG12C mutations more often than their female counterparts.12 Moreover, the predominantly truncal nature of KRASG12C makes this mutation persistent during disease progression.13,14 “It’s important to know that the KRAS mutation can actually occur in any patient, regardless of smoking status or race,” emphasized Dr. Li.

While there are various chemotherapy and immunotherapy treatment options for advanced or metastatic NSCLC, Asian patients with KRASG12C mutations are still subjected to poor survival outcomes similar to those absent of KRAS mutations.15 From the LC-SCRUM trial, it was revealed that the overall survival was not significantly different between patients with KRASG12C-mutated nonsquamous NSCLC and patients who were KRASWT/non-driver (26.7 vs. 22.4 months; p=0.35).15 For the existing second-line treatment regimens for KRAS mutated NSCLC, whether it be programmed death 1 (PD-1) inhibitor monotherapy such as nivolumab, pembrolizumab or atezolizumab, the PD-1 inhibitor ramucirumab plus docetaxel, or docetaxel monotherapy, all of which can only confer a progression-free survival (PFS) of less than 5 months.16-19 Moreover, Dr. Li reminded, “The second-line chemotherapies are full of toxicities that we have to manage daily as part of our job as an oncologist. Although the immune checkpoint inhibitors come with adverse effects that can be better managed, the treatment options are pretty limited.” This has thus highlighted the need of more robust and well-tolerated therapies for advanced or metastatic NSCLC patients, and specifically for those with KRAS mutation.

CodeBreak 100 clinical trials: Sotorasib shows a favorable efficacy and safety profile

Though the direct inhibition of KRAS could be challenging considering the lack of surface targets for binding and the non-selectivity towards KRASWT, pinpointing the KRASG12C mutation specifically has instead created a cryptic, targetable pocket on KRAS.20-22 One such example is sotorasib, the first-in-class KRASG12C inhibitor that forms a permanent covalent bond with the cystine moiety of the mutated KRASG12C protein, abolishing its affinity to guanosine-triphosphate (GTP) and hence rendering it inactive.4,22 In addition to its preclinical chemical properties, sotorasib has also been studied for its safety and efficacy in human cancer patients in the CodeBreak 100 trials.

Phase 1 of CodeBreak 100 was a multicenter, open-label, dose escalation and expansion trial that primarily assessed the safety outcomes in patients with advanced solid tumors harboring the KRASG12C mutation.23 A total of 129 cancer patients, including 59 patients with NSCLC, received oral sotorasib once daily with a dose escalation from 180mg to 960mg.23 These patients had received a median of 3 previous lines of anticancer therapies for metastatic disease.23 In terms of safety, sotorasib monotherapy demonstrated a favorable safety profile with no dose-limiting toxic effects or treatment-related deaths.23 Only 15 patients (11.6%) reported grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs), which were mostly related to elevated liver enzymes and diarrhea.23

Additionally, efficacy analysis indicated that tumor shrinkage of any magnitude was observed in 42 patients (71.2%) during the first assessment at week 6.23 The change from baseline tumor burden was evident across all dose levels.23 The median duration of response was 10.9 months, with a median duration of stable disease of 4.0 months.23 In particular, for the 34 patients receiving 960mg sotorasib, 35.3% had a confirmed response and 91.2% had disease control.23 Overall, the median PFS for all NSCLC patients was 6.3 months.23 “The results showed that the durability of response [of sotorasib] was very good,” remarked Dr. Li.

Following the phase 1 trial, the CodeBreak 100 phase 2, multicenter, single-group, open-label study continued to evaluate the efficacy and safety of once-daily 960mg oral sotorasib in patients with KRASG12C-mutated advanced NSCLC previously treated with standard therapies.24 The study recruited 126 patients, of which 81.0% had previously received both platinum-based chemotherapy and PD-1 inhibitors.24

The results revealed that, of the 124 patients evaluated for response, 46 patients had an objective response (OR; 37.1%; 95% CI: 28.6-46.2), where 4 patients (3.2%) achieved complete response and 42 patients (33.9%) achieved partial response.24 Notably, disease control was achieved by 80.6% (95% Cl: 72.6-87.2) of patients.24 Tumor shrinkage of any magnitude was observed in 82.3% of patients (102/124). Median best percentage decrease from baseline in tumor burden was 60%.24

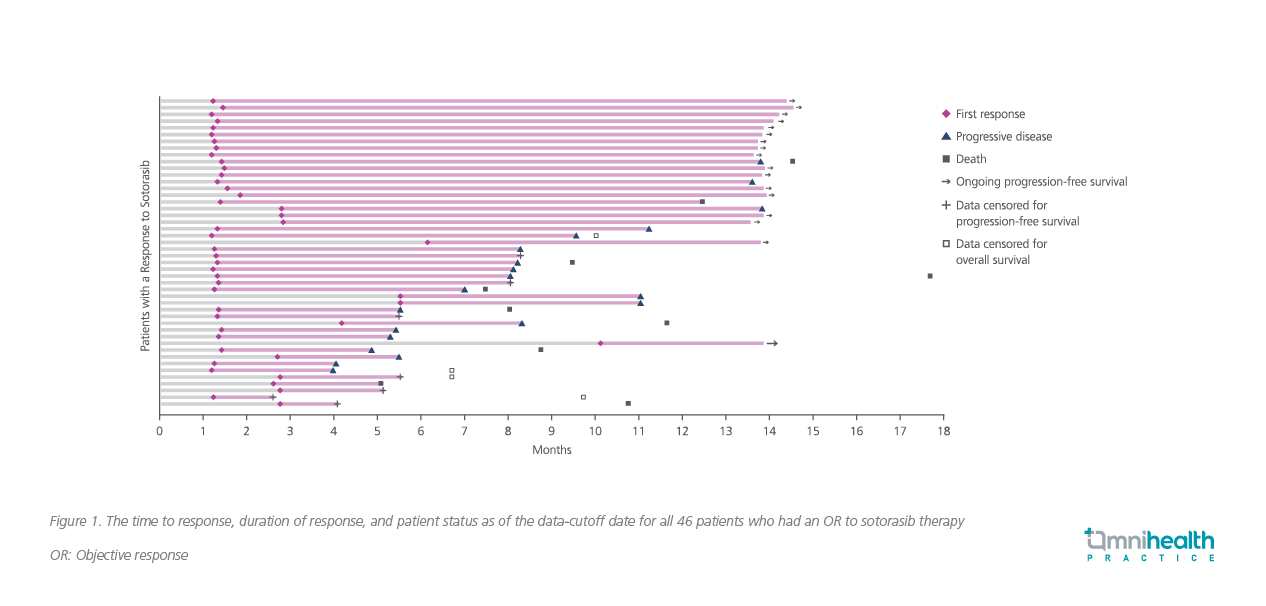

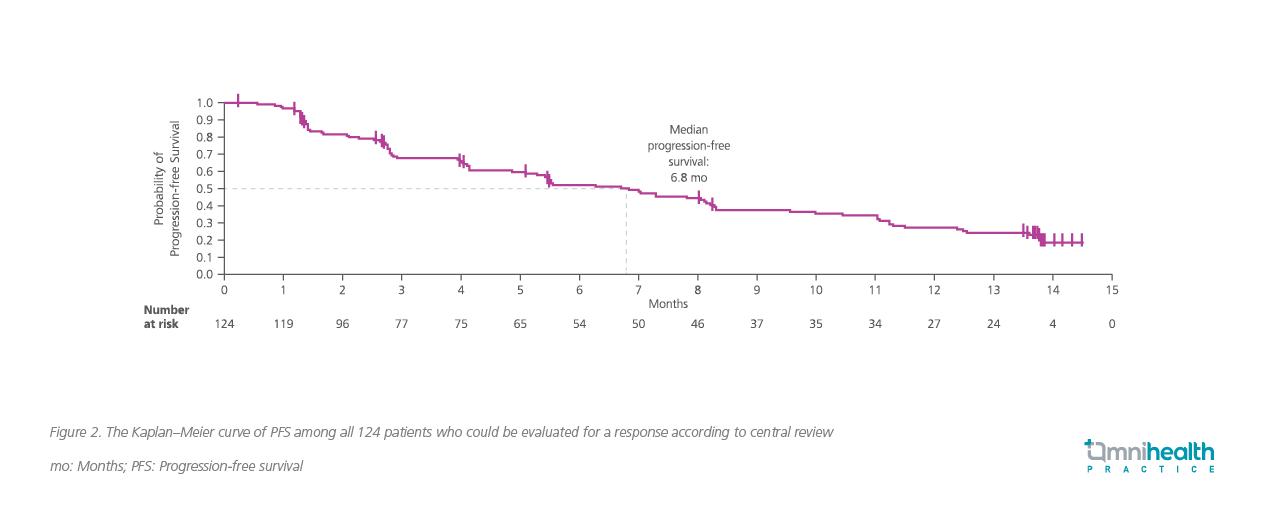

The median time to OR was 1.4 months, while the median duration of response was 11.1 months (95% Cl: 6.9-could not be evaluated) (Figure 1).24 As early as week 6, 71.7% of patients showed a response during the first assessment.24 Among the responders, 34.7% (16/46) also remained on treatment without progression as of the data cutoff.24 Overall, patients achieved a median PFS of 6.8 months with sotorasib (95% CI: 5.1-8.2; Figure 2).24

In terms of safety, the majority of the TRAEs belonged to either grade 1 or 2, with no fatal TRAEs being recorded.24 Treatment discontinuation due to TRAE was seen in only 7.1% of patients.24 Dr. Li thus summarized, “[The efficacy results of the phase 2 trial] were very similar to that of phase 1. And, no surprise, in terms of the adverse events, [they were] similar to that in the phase 1 study.”

In connection with these positive findings, the FDA has granted accelerated approval to sotorasib on May 28, 2021 for treating adult patients with KRASG12C-mutated, locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC as determined by an FDA‑approved test, who have received at least one prior systemic therapy.5

Testing for KRASG12C mutation for NSCLC is necessary

Given the favorable data substantiating sotorasib as a new treatment standard, it now becomes important to proactively identify KRASG12C during mutation testing. Yet, Dr. Li observed that the testing rates for KRASG12C remain suboptimal, citing the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) Survey on Molecular Testing which showed that only 61% of clinicians in the US/Canada would order KRAS mutation testing for lung cancer patients, lagging behind the testing rates of other biomarkers such as EGFR mutation (96%) and ALK rearrangements (93%).25 Therefore, Dr. Li recommended, “As KRASG12C is part of the [genetic testing] panel, I would certainly advocate for KRAS testing routinely.”

To detect KRASG12C, Dr. Li suggested that next generation sequencing (NGS) can be employed to simultaneously capture the multiple actionable mutations for targeted therapies. Alternatively, PCR followed by Sanger sequencing is also possible.26 The FDA-approved diagnostic kits are also available for sample preparation for clinical diagnostic purposes, such as FoundationOne CDx and OncomineTM Dx Target Test.27,28 It is estimated that the turn-around time (TAT) for detection by single gene PCR will be around 1 to 7 days whereas that for NGS will be 7 to 20 days.29 Though the TAT of NGS is much longer than that of PCR, Dr. Li emphasized that an extended NGS panel should be ordered at diagnosis to screen for possible KRASG12C mutation so that patients can immediately benefit from sotorasib when disease progresses on first-line treatment.

When asked about the clinical treatment approaches for NSCLC patients who are positive for two or more driver oncogenes in NGS, Dr. Li explained that this is a rare phenomenon and would assess if both driver oncogenes are actionable with targeted therapies. He would first examine the patient’s demographics such as smoking history and then determine their relative clonality by assessing which driver oncogene has a higher variant allele fraction. If available, he would compare the variant allele fractions of the mutations in both tissue biopsy and plasma DNA, which may infer whether the driver oncogene is truncal clonal or sub-clonal. After collecting this information, he will choose the drug which targets the predominant clonal oncogene.

Conclusions

While being considered undruggable for nearly 4 decades, KRAS has now become an actionable oncogenic driver in lung cancers and has given rise to sotorasib, the first-in-class KRASG12C inhibitor with encouraging safety and efficacy as demonstrated in both the phase 1 and phase 2 CodeBreak 100 trials. To help fully apply the benefits of sotorasib in the clinical setting, KRAS testing should become a routine practice for all patients with advanced NSCLC. Overall, given its favorable clinical data, sotorasib holds the potential to address the unmet needs in the second-line treatment setting of advanced or metastatic NSCLC where chemotherapy and immunotherapy options are associated with limited survival benefits.