CASE REVIEW

A case sharing: When untreated hypothyroidism manifests with macroglossia and mimics muscular pseudohypertrophy in Kocher-Debré-Semelaigne syndrome

Kocher-Debré-Semelaigne syndrome (KDSS) is a rare but distinct pediatric manifestation of long-standing untreated moderate-to-severe hypothyroidism, characterized by muscular pseudohypertrophy alongside classical hypothyroid features.1-3 While thyroid hormone replacement can reverse most clinical and biochemical abnormalities, delayed recognition may lead to prolonged morbidity.2,4 In this case shared with Omnihealth Practice, Dr. Zaatil Iffah Asmawi reported a 4-year 4-month-old boy with known congenital hypothyroidism (CH) who had defaulted follow-up. He presented with progressive macroglossia causing feeding and speech difficulties, poor growth, moderate neurodevelopmental delay, and coarse facial features. Examination revealed muscular pseudohypertrophy of the calves, thighs, shoulders and back. His dramatic response to levothyroxine highlights the importance of recognizing late complications of CH through careful clinical evaluation and ensuring long-term therapy adherence.

Background

KDSS is an uncommon yet striking manifestation of long-standing moderate-to-severe hypothyroidism in childhood.1-4 First described by Kocher in 1892 and later detailed by Debré and Semelaigne in 1935, the syndrome is characterized by muscular pseudohypertrophy in the setting of untreated congenital or acquired hypothyroidism.1,2,4 While hypothyroidism is a well-recognized endocrine disorder in pediatrics, its presentation with striking neuromuscular features often leads to diagnostic confusion with primary

myopathies such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD).2 Early recognition is therefore crucial, as KDSS represents one of the few reversible causes of muscle hypertrophy, with thyroid hormone replacement leading to rapid biochemical and clinical recovery.1-3

Thyroid hormones are central to normal growth, development, and metabolic regulation.5 In skeletal muscle, they regulate mitochondrial activity, gluconeogenesis, and the balance of protein synthesis and degradation.6 In hypothyroid states, impaired mitochondrial oxidative metabolism together with intramuscular deposition of glycogen contributes to myopathy and pseudohypertrophy.2,3 Notably, only about 10% of patients with hypothyroid myopathy develop muscular hypertrophy, underscoring the unusual nature of KDSS. The hypertrophied muscles are typically enlarged and firm, often giving an appearance reminiscent of primary muscular dystrophy.2,4 Distinguishing these cases relies on thyroid function testing, where low free thyroxine (T4) and elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels confirm primary hypothyroidism.5

The hallmark clinical feature of KDSS is muscular pseudohypertrophy, typically affecting the calves and thigh muscles. The tongue may be enlarged, and facial features may appear coarse or puffy.1,2,4 Children often present with lassitude, poor growth, coarse facial features, dry and thickened skin, and delayed developmental milestones.1-4 Anemia and delayed bone age are commonly reported systemic associations.4 In some cases, presenting complaints may revolve around exercise

intolerance, difficulty walking, or concerns related to calves’ enlargement, which can further mislead clinicians toward a neuromuscular diagnosis.2,4 Neurologically, affected children may exhibit hypotonia, reduced muscle power and delayed relaxation of tendon reflexes, despite the apparent muscle bulk.1,2,4,7 Collectively, these manifestations reflect the underlying untreated hypothyroidism characteristic of KDSS.5

Although the true incidence of KDSS is unknown, the condition is considered rare, with most cases reported in regions where CH screening is inconsistent or follow-up is interrupted.1,3 In this case, Dr. Zaatil demonstrates that missed follow-up in a child with known CH may allow classic KDSS features to emerge, emphasizing the need for vigilant follow-up and continued therapy.

Case sharing

A 4-year-4-month-old boy with CH diagnosed at birth (cord TSH 450mIU/L) presented with a progressively enlarging tongue, swelling under the chin, increasing fatigue, and poor growth. He had previously been on levothyroxine 50-75μg daily but defaulted follow-up and therapy from 1 year 10 months, as his parents attributed coincidental childhood illnesses to the medication. On further history, parents reported feeding difficulties over the past year, particularly with solid foods such as rice, and difficulty brushing his teeth. He also had chronic constipation, with bowel movements every 3-4 days, occasional straining, and minimal blood noted at times, as well as cold intolerance, being unable to bathe even in the afternoon. Growth had been poor, with a height increment of only 1cm per year. Developmental milestones were moderately affected: gross motor ~2 years, fine motor ~2 years, speech ~2.5-3 years, and social skills ~2.5-3 years.

On examination, the child appeared short and underweight for age (height 85cm, weight <3rd percentile) with mild pallor and a sluggish appearance. He had a puffy, coarse facial appearance and periorbital edema (figure 1). The tongue was enlarged and firm, unable to protrude fully, with minimal dental caries and oral candidiasis. Firm to hard swelling was noted under the submandibular region. Macroglossia contributed to muffled speech. Muscle pseudohypertrophy was observed in arms, upper back, and lower limbs, with reduced tone in the fingers (power 4/5). The abdomen was distended but soft, with some palpable fecal mass; no hernia was noted. Skin was dry, coarse, and wrinkly, particularly over the hands. Heart rate was bradycardic for age–other cardiovascular and respiratory examination were unremarkable (heart rate 70bpm, no murmurs; lungs clear). Neurologically, tone was mildly reduced and reflexes showed delayed relaxation.

Laboratory findings were consistent with profound hypothyroidism (TSH 912.81mIU/L, free T4 <5.41pmol/L, free T3 <1.46pmol/L) and hypothyroid-induced myopathy (CK 1,834U/L). Electrolytes and renal function were largely normal, with mildly elevated creatinine. Liver function tests showed mild elevations (ALT 46U/L, AST 121U/L), while albumin and ALP were within normal limits.

The child was restarted on oral levothyroxine 50μg daily (3.8μg/kg/day), with gradual up-titration. Two weeks later, TSH had declined to 242.98mIU/L, with corresponding rises in free T4 (14.54pmol/L) and free T3 (6.30pmol/L). Given the partial biochemical response but persistently elevated TSH, the dose was increased to 62.5μg daily (4.8μg/kg/day). Subsequent follow-up after another two weeks demonstrated normalized TSH at 3.85mIU/L, free T4 of 17.63pmol/L, and free T3 of 8.43pmol/L. CK had returned to 134U/L, and liver function tests and electrolytes had also normalized, confirming effective restoration of thyroid function and improvement in hypothyroid-related myopathy.

The child was also noted to have moderate normocytic, normochromic anemia (Hb 8.6g/dL, MCV 86fL, MCH 27pg, MCHC 31g/dL, RDW 12.8%). Peripheral blood film suggested anemia of chronic disease, likely due to nutritional compromise from feeding difficulties caused by macroglossia, compounded by the systemic effects of long-standing hypothyroidism. Serum iron was borderline (11.6μmol/L), hence the child was started on iron supplementation (3mg/kg elemental iron). Nutritional

support was optimized, with gradual improvement in hemoglobin expected alongside continued thyroid hormone replacement.

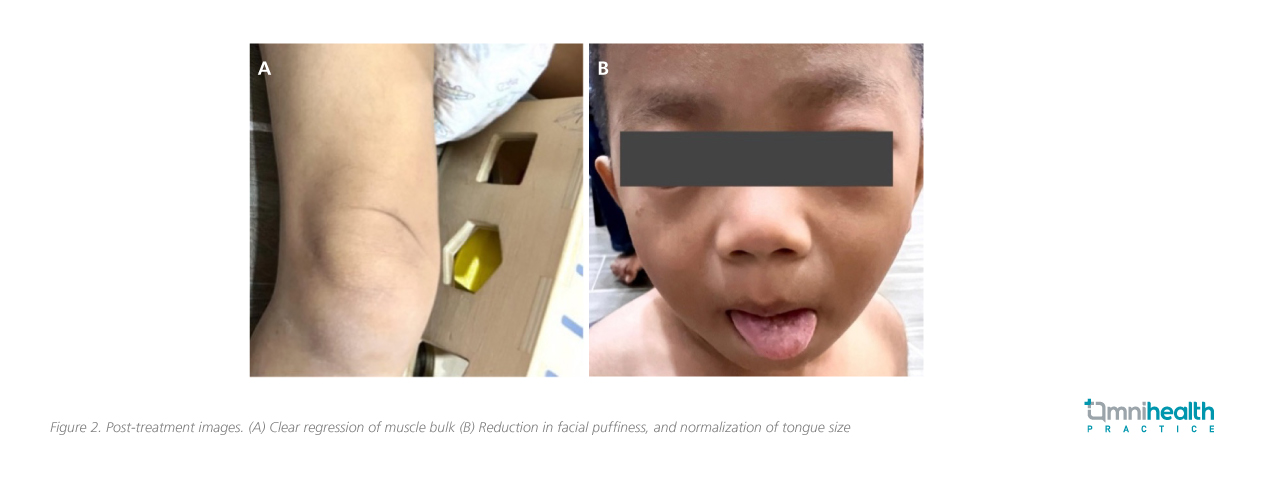

Clinically, the child exhibited dramatic improvement: macroglossia regressed, facial puffiness resolved, and calves hypertrophy diminished, with parents noting enhanced energy, appetite, and clearer speech (figure 2). Muscle tone and reflexes normalized, and the child was able to ambulate, run, and climb stairs without difficulty. Developmental progress included gross motor ~2.5 years, fine motor ~2 years, speech ~3 years, and social skills ~3 years. Constipation resolved, with daily soft stools (Bristol 2-3), cold intolerance improved, and anthropometric measures demonstrated catch-up growth. Heart rate has also gradually normalized to 100-120 bpm following normalization of thyroxine level.

Discussion

This case illustrates the classic presentation of KDSS, where muscular pseudohypertrophy coexists with systemic features of hypothyroidism.1-3 As Dr. Zaatil notes, “The child’s history of CH and interrupted therapy, together with characteristic features such as coarse facies, macroglossia, and delayed reflexes, steered the diagnosis toward endocrinological causes. A simple thyroid function test is essential in children with unexplained muscular features, allowing rapid diagnosis of complications such as KDSS.”

The diagnosis of KDSS rests on demonstrating moderate-to-severe primary hypothyroidism in a child with muscle pseudohypertrophy.1-3 Laboratory features include a markedly elevated serum TSH, profoundly reduced fT4 and fT3, and frequently elevated CK, consistent with an underlying myopathy.1-5 Ancillary investigations may reveal reversible derangements in liver function tests and/or anemia.2,4 Echocardiography may reveal pericardial effusion, particularly in long-standing hypothyroidism, while radiographs for bone age assessment often demonstrate delayed bone maturation.4,8 Differential diagnoses may include DMD,

mucopolysaccharidosis, and other metabolic myopathies.2,9 Unlike these genetic disorders, KDSS syndrome responds rapidly and dramatically to thyroid hormone replacement therapy.¹

The defining feature of KDSS is elevated CK levels, suggestive of the underlying hypothyroid-induced myopathy.1-4 CK normalization following levothyroxine supported the reversibility of muscle involvement.2 Liver enzyme derangements, also corrected with therapy, were consistent with reversible metabolic effects of hypothyroidism.2,4 The anemia observed in this case further underscores the systemic nature of thyroid deficiency, with mechanisms involving reduced erythropoietin production, marrow suppression, and nutritional inadequacies due to

macroglossia-related feeding difficulties.10

The treatment of KDSS is straightforward: levothyroxine therapy titrated to achieve biochemical euthyroidism.1,2 As observed in this case, Dr. Zaatil explains that the child’s rapid improvement in thyroid function and clinical phenotype following levothyroxine highlights the condition’s reversibility. The dramatic regression of macroglossia and calf hypertrophy reinforces the importance of timely recognition and intervention. While the immediate priority was thyroid hormone replacement, determining the underlying etiology of hypothyroidism remains clinically relevant

to guide long-term management and prognosis.3,9

Importantly, this case also illustrates the long-term consequences of delayed diagnosis and treatment of CH. Despite dramatic improvement in muscle and metabolic features, the child experienced extended periods of untreated hypothyroidism during critical developmental windows. As Dr. Zaatil notes, once developmental delay and growth stunting set in, these complications are not fully reversible. Within the next six months, the child’s cognitive and learning abilities will be further assessed, but some degree of intellectual disability is anticipated. Current growth parameters remain severely stunted, emphasizing the impact of delayed presentation and long-term hypothyroidism on linear growth and overall

development.

Overall, KDSS remains a rare entity, with only scattered case reports and small series in the literature.1-3 Hence, delays in recognition can result in irreversible consequences such as impaired linear growth, persistent neurocognitive deficits, or skeletal deformities.3 Unlike dystrophinopathies, however, KDSS is generally non-progressive and often reversible, with notable improvement following thyroid hormone replacement.2

Dr. Zaatil also reflects on the clinical lessons from the case:

- Catch it early, treat it right: Timely diagnosis and optimal titration of thyroid hormone in CH are essential to support growth and prevent irreversible neurodevelopmental delays during the critical brain development period

- Knowledge is prevention: Educating parents and the public on continued thyroid hormone therapy reduces missed follow-ups and prevents late complications such as KDSS

- Think thyroid, not dystrophy: Unexplained muscle enlargement or macroglossia accompanied by hypothyroid features should prompt thyroid testing, as KDSS can mimic muscular dystrophy

- Reversible if recognized: KDSS manifestations respond well to levothyroxine, highlighting the importance of timely recognition and treatment

Conclusion

KDSS syndrome represents a rare but classical manifestation of llong-standing pediatric hypothyroidism, with distinctive features that can easily be mistaken for neuromuscular disease.1-3 This case highlights the importance of clinical vigilance and the role of thyroid function testing in children with muscular hypertrophy and multisystem involvement.1,2 Prompt initiation of levothyroxine not only normalizes biochemical abnormalities but also leads to dramatic clinical recovery, as demonstrated by the resolution of macroglossia, calf hypertrophy, and systemic features in this case.2,7 Ultimately, the broader lesson is clear: endocrine disorders can masquerade as neuromuscular conditions, and early recognition of this syndrome ensures excellent outcomes while sparing children from unnecessary investigations and prolonged morbidity.1-4

“A simple thyroid function test is essential in children with unexplained muscular features, allowing rapid diagnosis of complications such as KDSS”

Dr. Zaatil Iffah Asmawi

Consultant Pediatrician,

Stepping Stones Child Specialist Clinic,

Terengganu, Malaysia